How to Address Digital Equity

The Consortium for School Networking (CoSN) has developed some best practice strategies for schools looking to directly address the issues of digital equity. Below is an executive summary of the most recent update to its Digital Equity Initiative Toolkit. For the full list, go to https://cosn.org/DEtoolkit.

During the past two decades, efforts to provide America’s schools with high speed Internet access have made great progress. Supported by the 2014 modernization of the federal government’s E-Rate program and state funding efforts, a majority of schools now meet the FCC’s short term connectivity goal of 100 Mbps/1000 students.

However, the increasingly ubiquitous use of technology in instruction has resulted in a new digital divide between students who have home Internet access and those who do not. This “Homework Gap,” which impacts low-income and rural students especially hard, can exacerbate other preexisting inequalities, making it difficult for students to complete homework assignments. The lack of home Internet access also negatively impacts school/parent communication and makes it more difficult for parents to support their children academically.

The COSN Digital Equity toolkit provides background context for the Homework Gap, addresses broader implications of household connectivity, suggests resources for scoping the problem, and details five strategies districts are currently using to address these challenges:

1. Partner with Community Organizations to Create “Homework Hotspots”

2. Promote Low Cost Broadband Offerings

3. Deploy Mobile Hotspot Programs

4. Install Wifi on School Buses

5. Build Private LTE Networks

In addition, COSN outlines four steps school leaders can take to collaborate with local governments and their community to take a broader, more holistic approach to digital access and inclusion:

1. Assemble a Team and Develop a Shared Vision

2. Assess Existing Community Resources, Gaps and Needs

3. Engage Stakeholders and Partners

4. Develop and Execute a Project Plan

Tech & Learning Newsletter

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Access to reliable, robust Internet service and computers are increasingly essential for learning and participation in modern society and should not be a luxury reserved for the affluent. Innovative school and district leaders are rising above fiscal constraints to ensure students have broadband access both during and beyond the school day. While there is no single way to address these challenges, this toolkit provides best practices and resources to help school officials develop digital equity solutions that work for their communities.

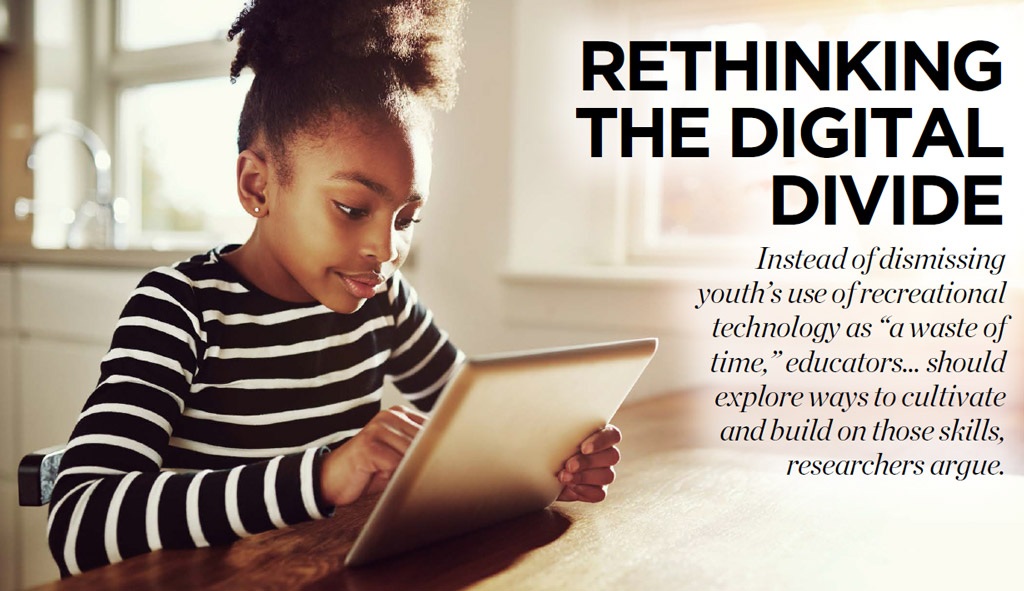

Parents of teenagers today often complain their children are “addicted” to technology, spending too much time playing video games and watching YouTube videos, according to a recent report on Pullias Center for Higher Education. For black youth, such criticisms about their technology use come not just from family members, but from educational researchers too.

That is one the findings of a newly-published study in Howard University’s The Journal of Negro Education. The two authors found, for example, that because black teens are more likely than their white and Asian counterparts to use their phones and computers for gaming and cartoon watching, some researchers assumed that “black youth are making decisions counter to their academic growth.” But the answer isn’t that cut and dry, according to the study’s authors.

“While black youth are less likely to use their computers and cell phones for educational purposes, this doesn’t mean these youth don’t have an interest in education,” said Antar Tichavakunda, assistant professor of education leadership at the University of Cincinnati and a research associate of the Pullias Center. “The real issue could be that the content on educational sites was not made to appeal to or connect with this population group.”

According to the authors, educators and researchers should refrain from jumping to limiting conclusions, and instead study the digital practices of black students more carefully through a cultural lens. That would allow for more creative and effective ideas for helping these youth use their tech tools toward more productive ends—by building on the skills and habits they already possess.

“I think we’re missing some important educational opportunities by assuming certain ways of using technology are inherently unproductive or undesirable,” explained William G. Tierney, co-director of the USC Pullias Center for Higher Education and Wilbur Kieffer Professor of Higher Education at USC Rossier School of Education. “If we instead take the perspective that we can learn from and build on the ways black students are already engaging with technology, our efforts would have more resonance and success.”

Tichavakunda and Tierney pointed out that a more positive focus on the digital skills black students bring to the table could change both the questions educational researchers ask and the conclusions they draw.

This study continues Tichavakunda’s and Tierney’s work investigating digital equity and college readiness for underserved students. Tierney is a member of the Pullias Center’s Digital Equity in Education team, which recently received a $300,000 grant from the ECMC Foundation to develop a digital tool to help decrease summer melt and improve first-year persistence rates at California State University Dominguez Hills.