On Balance (by Kevin Jarrett)

{Cross posted on Welcome to NCS-Tech!}

photo credit: pshutterbug

How often have you heard a colleague (or family member, for that matter) say:

"Can you give me a hand with [insert random technology task] ?"

The answer, for most of the people reading this, I'll bet: more times than we can count. I found myself wondering about this the recently, contemplating the many times I've been given busy teachers just-in-time solutions to whatever technological challenge they happened to face at any particular moment. But what was most interesting to me, this time, was that I was not reflecting on the specific bit of technical knowledge these teachers lacked (i.e.: shouldn't they know this?), but rather, the enormous, immeasurable, expansive knowledge base they DID have (i.e.: on teaching and learning, classroom management, differentiated instruction, curriculum, assessment, learning styles, etc.) - the intersection between the technology need and their instructional objective. That's when it hit me. We're out of balance. All of us, to one extent or another, could really benefit by focusing less of the things we know well and more on the things we don't. It's the essence of personal/professional growth. But it's more than just learning new things.

photo credit: Brian Hillegas

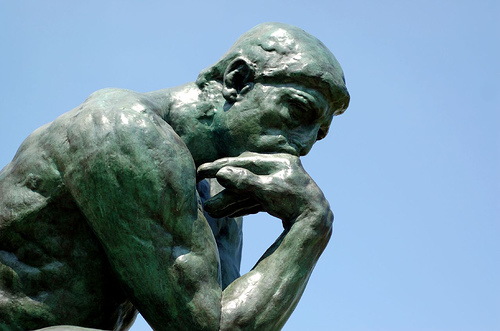

In their book Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, authors Chip and Dan Heath talk about what they call the "Curse of Knowledge," conveniently excerpted here on the 37Signals blog:

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

"Lots of research in economics and psychology shows that when we know something, it becomes hard for us to imagine not knowing it. As a result, we become lousy communicators. Think of a lawyer who can’t give you a straight, comprehensible answer to a legal question. His vast knowledge and experience renders him unable to fathom how little you know. So when he talks to you, he talks in abstractions that you can’t follow. And we’re all like the lawyer in our own domain of expertise."

It's happened to every "techie" at one time or another. You're in a conversation, trying to explain a complex task or program feature, and the person you are helping just isn't getting it.

- "You're going too fast."

- "I'm sorry, I don't understand."

- "I'll never be 'as good with technology' as you."

Sigh. My friend and colleague Kim Cofino touched on this back in December 2009 with her excellent blog post Making the Implicit Explicit. I love her list of "those almost unidentifiable skills that frequent computer users just seem to take for granted." I never really thought about it before I read her post but she is so right. She reflects:

What’s especially interesting about these little, seemingly meaningless, skills is that they truly are transferrable and haven’t changed much over time – they’re certainly not dependent on a specific version of software. Unfortunately, despite their consistency, they often cause a lot of confusion for people who aren’t really comfortable with technology.

She continues:

We simply expect people to know why the mouse and cursor change shape and what the shapes mean, or that you can figure out how to do pretty much anything by checking the help menu in any program, or that you need to highlight something before being able to change that item because that’s how you “tell” the computer what you want to change. These have become intuitive skills for those of us that use technology regularly, but unfortunately not knowing them has become an obstacle for others to overcome.

All of this is mixing around in my head right now thanks to my neurological Cusinart (quick, someone press 'Purée.') What are the implications for us as teachers (of students), mentors (of peers), and learners (for ourselves)? I don't have answers. I have questions.

- What do we assume people know when we are providing support, answering a question, or teaching a lesson? (Formative assessment? Hello?)

- Do master teachers possess innate skills that allow them to instantly & effortlessly change their delivery for different learners struggling with different aspects of a particular topic?

- How do you approach a complex, broad, multifaceted topic in a meaningful but casual conversation? Sort of like me asking a veteran colleague about "classroom management," and someone asking me about "Web 2.0."

What do you think? -kj-