I’m Not an Expert, But Neither Are You Part 2

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

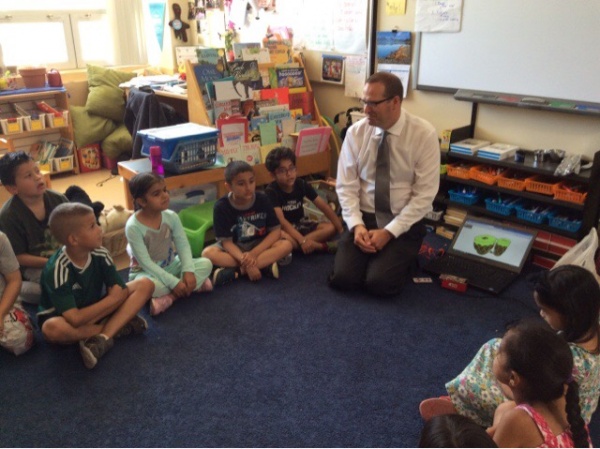

Photo by Karen Lirenman

Yesterday’s post was intended to challenge teachers for the most not to be swayed by those who have either been given or taken the title of an expert. Anyone who spends any time working with children and helping them learn brings with them a reasonable level of expertise to be able to contribute to the conversation and question authority.

While my context was largely about online spaces I think it’s important to examine and apply this more locally. In particular, how do schools and districts work to either include teachers as experts or suggest teachers need to see those higher up on the org chart as having more expertise?

For as long as I’ve been in education, there were always those in leadership positions who were not respected and when they made suggestions or mandated policies they were met with eye rolls, furrowed brows, and heavy sighs usually behind their backs. Sometimes principals or superintendents were the least knowledgeable people about teaching and learning. They may have had administration and management skills but didn’t couldn’t discuss pedagogy, let alone pronounce it.

In our best schools and districts, this isn’t the case. Leaders, specifically principals are asked to be instructional leaders. I’ve been fortunate to witness many great leaders who indeed can have intelligent conversations about teaching and learning.

Having worked at the district level and continuing to work with people who directly support teaching and learning I can say that occasionally this is the group of district support personnel is often guilty of claiming expertise and lording it over teachers. They sometimes view teachers as resistant or antagonistic because they don’t easily adopt every new idea being tossed their way. Because these new ideas and initiatives are usually contrived and managed by district leaders, there comes a natural tension. While this tension may have many sources, I believe the fact that teachers are not seen as experts is a major cause.

What many district leaders have that many teachers do not is two things. First, they likely have taken courses, gone to conferences and read books on their specialties. Second, and it’s related to the first, they’ve had time. Time to reflect, time to articulate and process ideas. They’ve been given a luxury the average classroom teacher doesn’t have. I know, I was given and still have that luxury. While we can claim some knowledge, we still don’t have the day to day perspective of a classroom teacher. Yes, most of us were classroom teachers but we aren’t right now and every teacher, no matter how skilled they deserve the respect and acknowledgment of their own understandings and expertise. In fact, I believe it’s partly the job of those in leadership to provide the tools, space, and opportunities to see themselves as such.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

I’ve been fortunate to work on a team that has a horizontal leadership model. All voices are valid. In fact, science proves that the best teams are the ones where every voice matters. Schools and school districts can struggle in creating this kind of egalitarian environment. Yet I’ve seen it begin with the Superintendent. My favorite example of this is Jordan Tinney of Surrey Schools in BC.

Jordan is bright, articulate and passionate about teaching and learning. Many leaders of school districts of his size are relegated to CEO’s and are better at public relations than knowing much about the day to day happenings in classrooms. Not Jordan. A few years ago he dedicated himself to seeing first hand what innovation looked like in classrooms in Surrey. He spent the next few months visiting as many classrooms as he could. In essence, he was telling his teachers, “You an expert teacher, I want to learn from you”. I can tell you first hand these teachers and the entire district feels very much part of the conversation and are not intimidated by their leaders. Instead, they respect and value them and yet are willing to call out practices and policies that they feel might hinder learning. Jordan clearly sees his teachers as experts.

Of course, I’m using the term “expert” pretty broadly. As educators, we might say we have some level of expertise in teaching and learning. Our experience is as much part of this as our theoretical knowledge. If we maintain a reflective disposition this will grow over time. Some develop niche expertise in various areas of our craft. But no matter, all teachers can claim some degree of expertise and it needs to be acknowledged.

Let me say this, if you’re an educator and aren’t full of humility and acknowledge the complexity and challenge of doing your job, I’m not likely to grant you much respect.

I write and think often about district and school culture. I sometimes write about how valued you feel. This is directly tied to gratitude. I also talk about empowerment. This is tied to innovation. Expertise is related but also unique in that it’s about the ongoing work and progress about your school or district. So my questions are:

“Do you see yourself as an expert?

“Does your school/district acknowledge and take advantage of your expertise?”

cross-posted at ideasandthoughts.org

Dean Shareski is the Community Manager of the Canadian DEN (Discovery Educators Network) and lecturer for the University of Regina. With 24 years of experience as a K12 educator and consultant, he specializes in the use of technology in the classroom. Read more at ideasandthoughts.org.

Disclaimer: This weblog contains the opinions and ideas of Dean Shareski. While there may be references to my work and content which relates directly to my work, the ideas are mine alone and are not necessarily shared by my employer.