CREATING A CULTURE OF INNOVATION: AN EXCERPT FROM T&L LEADER

“You can’t mandate innovation,” says Joe Sanfelippo, superintendent of Fall Creek (WI) School District. “From an administrative standpoint, you have to create an environment in which people can take risks.”

That’s exactly what he and his staff have done. Instead of offering traditional professional development, Sanfelippo and a group of teachers brought the Google Genius Hour (www.geniushour.com)—Google engineers get to spend 20 percent of their time working on a pet project—to their district. They named it Passion Projects for Adults, and Fall Creek staff members get to learn about anything they want. “We’re trying to help people move to a different place without moving them,” says Sanfelippo.

To encourage teachers to explore, the district provides three essential ingredients: time, resources, and opportunity. This year, teachers received three student-free days to work on their projects. Principals know everyone’s passion goal so that they can connect teachers with the tools and other resources they need. As for opportunity, Sanfelippo says he’s always on the lookout, via social media and speaking engagements, for other schools that tie in with a passion project.

At the beginning of this school year, two teachers requested robotics kits. Sanfelippo suggested they first try using the Spheros, which are ball-shaped gaming devices that students program with a smartphone or tablet, in the library and connected them with a school in Minnesota that holds a Global Sphero Day. The teachers now have 25 Spheros and their students are programming and live-streaming for the community.

“Our intent is to embed everything we do in our culture. Last year, when we surveyed staff about our new professional learning model, 94 percent agreed or strongly agreed that it made them a better teacher.”

BE A PROBLEM SOLVER

When the word innovation is in your title, chances are you’ve got some insight on the topic. For Jennie Magiera, chief innovation officer at Des Plaines (IL) School District 62, one of the keys to creating an innovative culture is solving problems. “Remember that your colleagues are normal people who oftentimes can’t see beyond their pain points,” she says. “If you identify and alleviate that problem, you win. If you can do it in an innovative way, even better.” For example, when teachers complained about spending all of their time grading papers, Magiera made a Google Form to help them grade more efficiently. “If you make someone happy, you establish trust and demonstrate that technology can solve problems.”

Magiera is also strategic about which teachers to approach first. She acknowledges that a lot of people target the early adopters, but she goes straight to the laggards. “If you can convince the laggards, especially the loudest ones, to meet an early adopter or innovator and be turned into an innovator, that’s political gold and makes everyone else jump on board. They don’t want to be behind the laggards.”

When she launched a makerspace movement, Magiera decentralized making by bringing it to the classrooms instead of housing a space in the library. She recruited 10 teachers to be part of a cohort called the Dream Lab; they wrote a grant and bought 3D printers, virtual reality (VR) equipment, and other materials. Now the Dream Lab is exploring maker pedagogy, incorporating it into their core content, and writing lesson plans. They publish (bit.ly/62dreamlab) their lessons and teachers use a Google Form to check out maker materials.

BE VISIBLE

Two years ago, when John Martin began working at Inter-Lakes (NH) School District, his predecessor had just died. Understandably, there had been a gap in technology services for a couple of years. “The first thing I did was knock down a wall between my office and the administrators,” says Martin, director of innovation & technology. “Our office is in the high school and I didn’t want any barriers between me and the people I was trying to serve.” Martin wanted to encourage people to pop in and chat. “I needed to get traction to make any sort of innovations take off,” he says.

Today, the elementary school has a podcast club called the Blue Wave Broadcasters. The middle/high school has a LakerMaker space which, because it isn’t a scheduled room or tied directly to a classroom, allows students to explore technological questions outside of their classes. Martin’s latest project is getting a 360-degree camera so that students can begin working in VR settings. His office also hosts student interns who are exploring careers in computer science.

Martin’s technology staff knows that unless a request is potentially unsafe, their first word is never to be ‘no.’ As he says, “When you’re trying to get people engaged and to think about how to do things differently, it’s imperative to have a ‘Let’s talk this through’ attitude. It also lets people know that our concerns start and end with one question: How effective is their idea for students?”

Martin is also forming a technology leadership council to decide future plans. Their first task? Figuring out whether to replace a fleet of eight-year-old interactive whiteboards.

BE WILLING TO TRUST

“A lot of times, people think innovation means chaos. For us, innovation is strategic freedom,” says Vincent Scheivert, chief information officer for Albemarle County (VA) Public Schools. Scheivert says leaders need to decide what they are willing to give up and trust their students, teachers, and/or administrators to find more effective, efficient ways. “The death knell of any progressive organization is, ‘This is the way we’ve always done it,’ he says. “If you go into things with that mindset, you’ve defeated yourself.” Instead, do it differently from how you did it last year.

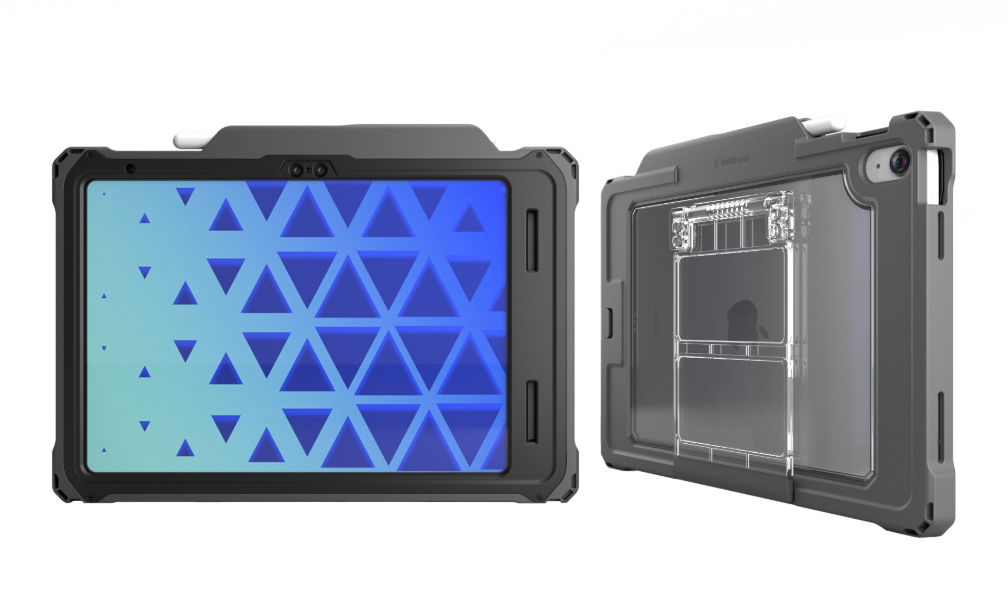

At Albemarle, every school has advanced manufacturing capabilities; many teachers let students choose their own style of seating. From the beginning of its 1:1 program in 2013, students were allowed to be full administrators of their devices. “We can’t call them personal learning devices if kids can’t personalize them, and that goes further than letting them select a background picture,” says Scheivert. Students add or delete programs and are expected to customize their laptops to suit their learning needs. The machines are content-filtered at school or on a home network, but students can access questionable sites as they learn. The beauty of this arrangement is that the mistakes students make are easily resolved. “We find that middle schoolers generally need a reimage once a quarter. By high school, that drops to one reimage in four years.”

Perhaps Albemarle’s biggest innovation is how they are solving the digital divide by building an LTE network to deliver public wireless network access to every home across the county’s 726 square miles. “By 2020, we want everyone to be able to access their tools, their homework, and any of our other resources,” says Scheivert. Even though the LTE initiative took a few iterations before it came together, he knows that is part of the process. “We try to fight saying no. Instead, we work through a process that allows us to get to that yes.”

Tech & Learning Newsletter

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.