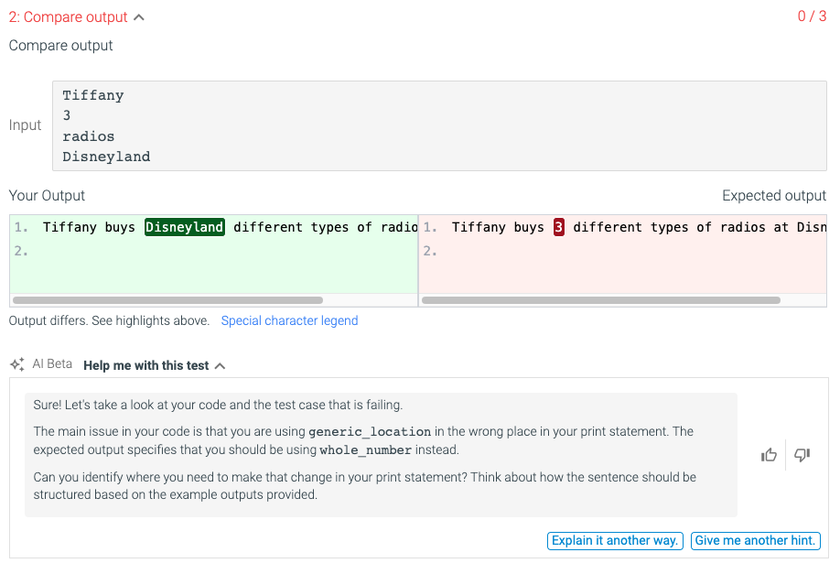

Why Aren’t Professors Taught to Teach?

Professors are experts in their subject matters but many have limited training in actually teaching their students.

Before teaching my first college class, the sum total of my pedological training consisted of a one-credit course taken during my first semester of graduate school.

In other words, like many college professors, when I started teaching I had never been taught to teach.

“A lot of faculty are just modeling their instruction after the instruction they've received as an undergraduate or graduate student,” says Tanya Joosten, senior scientist and director of digital learning at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the lead of the National Research Center for Distance Education and Technological Advancements.

That was certainly true in my case. I learned by trial and error, borrowing practices from my teachers that I enjoyed and which had seemingly worked for me. Sometimes this served me and my students well. I’ve always been drawn to individualized learning, a teaching practice that research, not surprisingly, confirms is effective. Other times it led me astray.

As a student, I hated short frequent assignments: give me one eight-page paper at the end of the month rather than four two-page papers due every week. However, research shows, and my experiences confirm, that students respond better to more frequent low-stakes assignments.

Ultimately, most higher ed professors are left to develop their own approach to instruction, which often leads to a wide range of learning outcomes, some of which are less than ideal.

A Cultural Shift Needed

Kathe Pelletier, director of teaching and learning at Educause, says that institutions that employ a master course model, in which each course, regardless of who teaches it, is built around learning objectives, do provide training to faculty. However, at more traditional universities it is left to individual professors to seek out the instructional designers and faculty development professionals on their own.

Tech & Learning Newsletter

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

“We need a cultural shift,” Pelletier says. “Institutions need to be honest about the fact that faculty don't come already prepared to teach; they are brilliant experts in their subject matters, but they don't have training. And it isn't necessarily a natural skill to know how to arrange your time with students so that it's spent most effectively and how to reach all types of students, no matter where they are starting from.”

As a perpetually short-on-time adjunct professor, I understand those who worry about mandatory training and required course reviews, but Pelletier stresses that she’s advocating for a more organic shift and that a top-down approach isn’t best. “That's not as collaborative and generative as really just embracing that we have these two different kinds of experts, one type of expert is an expert in their subject, and the other expert is an expert in teaching and learning,” she says. More attention is needed to meld these two kinds of expertise.

Tying More Incentives To Teaching

One challenge for many institutions is that there is little incentive for instructors to spend time improving their teaching. “People will tell you straight out that their focus is on their research, their tenure will be based on their research,” Joosten says. “People get tenure every day with [class] reviews that average 1.0 on a five point scale, because they produce research and produce development dollars through grants.”

She adds, “The system in post-secondary education and how it's situated needs to be transformed.”

Ultimately, Joosten would like to see tenure requirements updated to encompass more teaching metrics. In the meantime, she says universities should provide smaller rewards for their faculty members to study teaching.

“We need more opportunities for faculty across the campus, more incentives, like summer buyouts or stipends, for them to attend summer programs,” she says.

Individual faculty members can also take advantage of the existing resources on their campus by reaching out to the centers for teaching and learning within their universities and connecting with instructional designers, instructional technologists, and other pedagogy experts to build or revamp their syllabi.

Pelletier says that often such work begins with developing clear and realistic learning outcomes, then building assessments to measure those outcomes, and finally designing course lectures and other activities to support those outcomes. “So it’s really taking that backward design approach,” she says.

Movement In The Right Direction

The pandemic has caused many educators to reassess their teaching and identify the most important components, which has led to increased collaboration between instructors and others on campus, from IT professionals to librarians.

“One thing that's really promising is that institutions are increasingly recognizing the value of becoming much more student-centered, and really placing the student right in the center of their strategic planning and their mission,” Pelletier says.

This is certainly the case for me, and while putting students at the center of education doesn’t ensure all practices will be perfect, it is an important start and one that ensures, regardless of any detours or obstacles, your compass is always pointed in the right direction.

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.