T&L Leadership Summit Preview—The State of K-12 Cybersecurity/2019 Year in Review Released

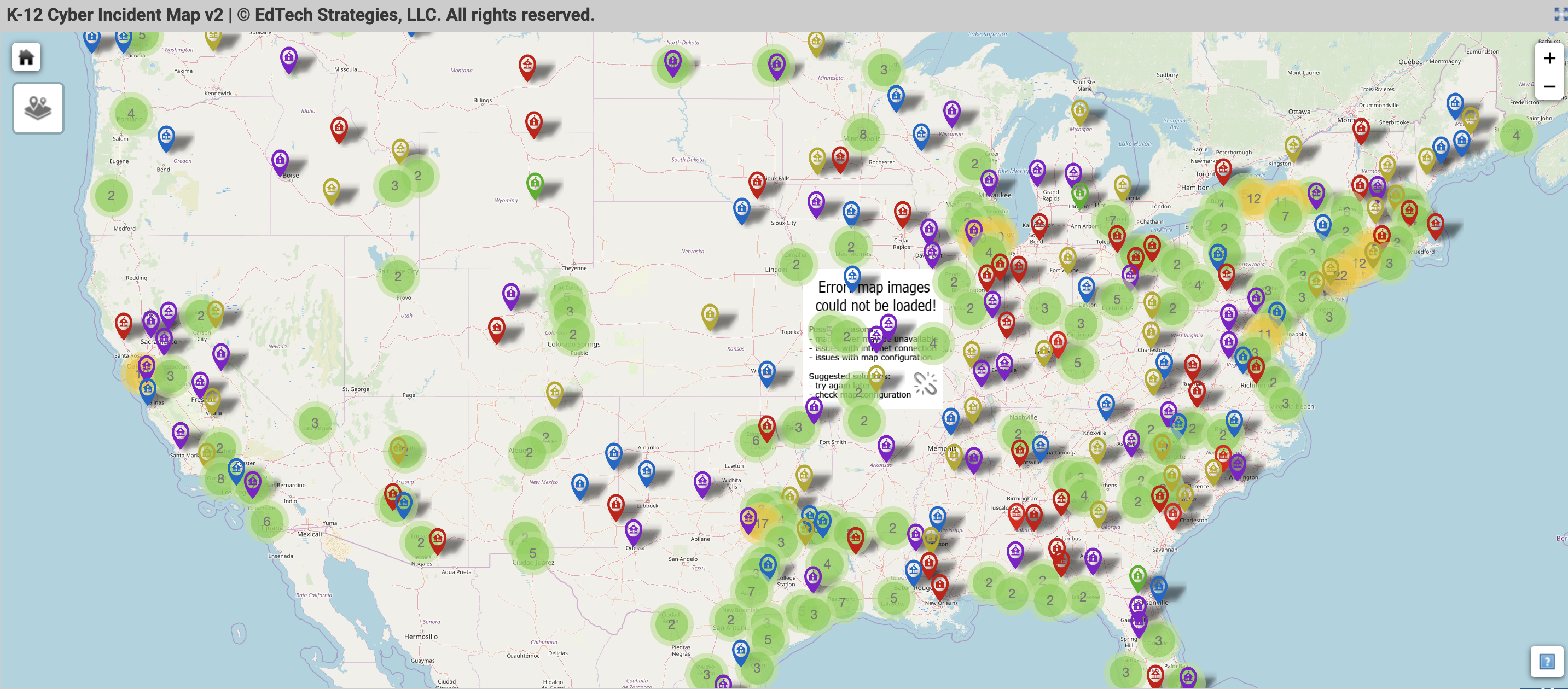

The countdown is on for the next Tech&Learning Leadership Summit in Washington, DC March 13 and 14 and Doug Levin, keynote speaker and founder of the K–12 Cyber Incident Map, has just released his annual report that identifies cybersecurity threats facing U.S. K–12 public schools and districts. His results will drive his session during the Summit. Each day this week, Tech&Learning will highlight parts of the report. For the full report, go to The K-12 Cybersecurity Resource Center

For all the benefits derived from using technology in schools, it also introduces new challenges. Among these challenges are those related to funding, teacher preparation and training, identifying best practices, and student health and well-being. While these concerns are generally well-understood (if often insufficiently addressed), there is an emerging challenge that appears to have caught many school districts off-guard: threats to the confidentiality, availability, and integrity of their data systems and technology from actors both known and unknown to the district. As Michael Melia of the Associated Press reports, “Schools with few or no employees dedicated to information security often are surprised to find themselves as targets.” This challenge is the challenge of K-12 cybersecurity.

During 2019, a nationwide cybersecurity survey of schools was conducted in the United Kingdom. Its findings – while not descriptive of the U.S. school experience – are nonetheless suggestive. Over 80 percent of UK schools reported having experienced at least one cybersecurity incident (with 10 percent of those reporting that their school had been “significantly disrupted” by an incident). At the same time, fewer than half of UK schools (49 percent) felt adequately prepared for a cyber attack or incident.

No such data exists about U.S. schools or districts. This report series – The State of K-12 Cybersecurity: Year in Review – aims to help remedy this gap by cataloging and analyzing data from every publicly-disclosed cybersecurity incident affecting public elementary and secondary education agencies across the U.S. It is the only research initiative of its kind and has grown to become the definitive source of statistics on K-12 cybersecurity incidents. The series is intended to spur greater attention to the challenges of securing school- (and school vendor/partner-) IT systems and suggest ways that policymakers and school district leaders might effectively respond.

Why is this report and research needed?

—Public reporting requirements for school cybersecurity incidents vary by state, but are generally quite weak. This lack of mandatory disclosure masks the severity and significance of the threats facing schools, leaves policymakers and school leaders without valuable information to guide their decision making, and leaves students, parents, and educators in the dark regarding the threats to which they may be exposed (whether in the past, present, or future). While there is a reasonable debate to be had about how transparent public agencies should be about their response to cybersecurity threats, the current state of information disclosure and sharing is anemic by any measure.

—Schools are increasing their reliance on technology for teaching, learning, and school operations. Indeed, the K-12 education technology market has grown to become very big business. This puts districts at greater risk for cybersecurity incidents, with many experts of the mind that it is not a matter of if any given school district will experience an incident, but when. Moreover, given that school district IT systems are interconnected with other local and state government agency systems (including public safety and election systems), this issue is salient to those whose purview typically excludes education policy.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

—As this report series documents, the frequency and severity of school cybersecurity incidents is increasing. Data held by school districts about students, families, and employees is sensitive, and while school districts don’t think of themselves as wealthy targets (given most are cash-strapped in providing services to the students in their care) the fact of the matter is that they manage the expenditure of large amounts of money every year to maintain facilities, provide transportation, food service, public health services, and education to large numbers of students. Without a coordinated, sector-wide response to the issue, it is hard to imagine any situation in which incident frequency and severity declines.