School Ventilation & Cognition: Air Quality Is About More Than Covid

The research is clear: improving school ventilation improves test scores and student cognition.

Improving ventilation and air quality in schools can do more than limit the spread of COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses, it can also help student performance.

In 2016, air filters were placed within schools located within five miles of a massive gas leak at a gas company in California’s San Fernando Valley. By the time the filters were installed a few months after the leak, there was no heightened pollution detected in those schools, but the filters still had a huge impact on student cognition. In a 2020 paper, Michael Gilraine, an economics professor at New York University, found student math scores in classrooms with filters went up by 0.20 standard deviations and English scores by 0.18 standard deviations.

The findings were not particularly surprising. “I was expecting quite large effects as some prior research, notably by Claudia Persico, has found large impacts of air pollution on test scores,” Gilraine says.

A 2017 review found “compelling evidence, from both cross-sectional and intervention studies, of an association of increased student performance with increased ventilation rates.” That was in addition to finding better ventilation associated with a decrease in respiratory viruses and school absences.

The impact of better air quality on human cognition has also been shown in more controlled settings.

A few years ago, researchers at the Healthy Buildings program at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health tested 24 participants who worked in conventional buildings or green buildings with better ventilation and air quality. Cognitive result scores were 61 percent higher in the green buildings and 101 percent higher in advanced green buildings.

“We have done studies, as others have, showing that higher ventilation rates and better filtration lead to improved cognitive function performance. This is not debatable at this point,” says Dr. Joseph G. Allen, director of the Healthy Buildings Program at Harvard and chair of The Lancet’s COVID-19 Commission Task Force on Safe Work, Safe Schools, and Safe Travel. “The positive impact of better air quality is seen across all ages, across all domains, -- reading, absenteeism, literacy -- and across countries.”

Tech & Learning Newsletter

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

He adds, “It's also obvious that air quality influences how we think and perform. Most adults have been in a stuffy conference room and you feel it -- you can't concentrate, you can't think, you feel tired, you sweat, you're looking at the clock. The door opens and life is literally and figuratively breathed back into the room.”

And students are not the only ones who benefit when schools increase ventilation.

“Staff retention increases or is associated with better ventilation,” says Dr. Gigi Kwik Gronvall, an immunologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and co-author of a report on ventilation in schools published by Johns Hopkins in May.

Improving Ventilation in Schools

Despite well-documented research into the benefits of good ventilation and the increased attention the issue has received during the pandemic, many schools remain poorly ventilated. “We've designed our schools and other buildings to bare minimum standards without health at the forefront,” Allen says. He adds, schools often fail to meet even these minimum standards. “We've neglected school infrastructure for decades.”

Plus, people are still getting the science wrong. “We have seen such rampant misinformation, even with COVID in air quality,” Gronvall says. “Some facility managers we've encountered have said, ‘Oh, we don't want to put portable HEPA filters in classrooms because they'll just move the COVID around.’ And it's like, ‘What? That's not even remotely accurate.’”

The good news is we know how to improve ventilation. “It's a fixable problem,” Gronvall says. She adds, it is a rare health intervention during the COVID era that has not yet become a partisan issue. “It's not like people don't want there to be good air in schools.”

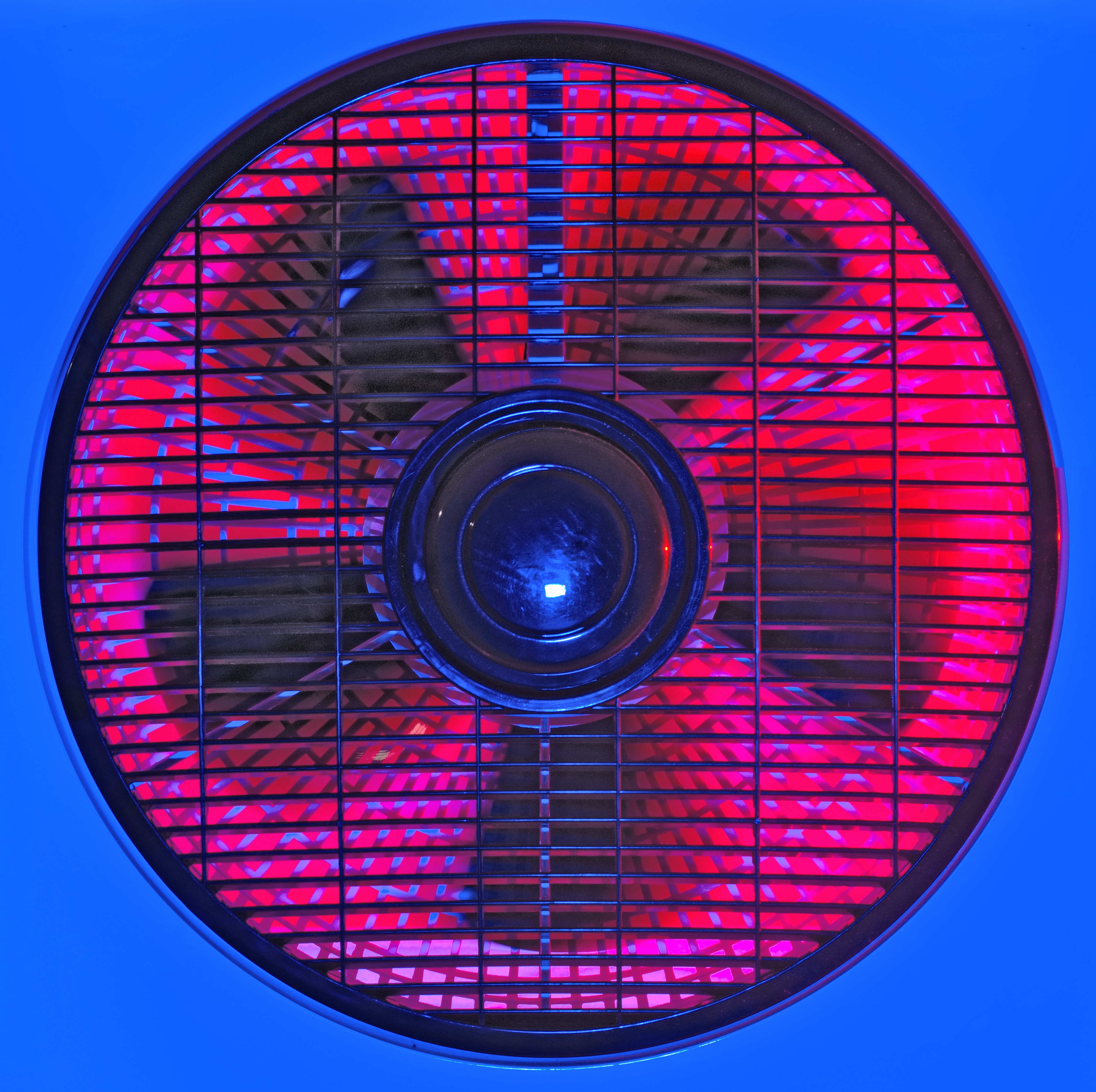

American Rescue Plan funds can be used to purchase portable HEPA filters, which is a good start, but funding can also help schools make larger structural ventilation improvements. Schools can also make quick ventilation improvements without spending thousands.

Gilraine says schools should be thinking beyond the immediate COVID crisis. “While a lot of the new funding for ventilation today is provided for COVID, educators should make sure that the ventilation systems are maintained even post-COVID,” he says.

The Johns Hopkins report calls for an interagency federal task force to help schools address air quality and provide clear guidance for improvements. “The Department of Education and the EPA needs to be doing more for schools in this area,” Gronvall says.

The time to act is now, say experts, as schools are already seeing increased ventilation challenges from rising temperatures.

“My big concern is that we're going to miss this moment to get it right,” Allen says. “Because the 40 years of neglect of our school infrastructure has taken a toll and we've never had the money available to make these fixes. If we don't do it, we'll be in trouble now during COVID, we'll be in trouble for regular flu season, we'll be in trouble because of lead in drinking water, we'll be in trouble for whatever pandemic comes next, and we'll be in trouble with a changing climate.”

Resources

- Harvard’s Healthy Buildings’ Schools for Health reports

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s School Ventilation report

- U.S. Department of Education guide on ways to use American Rescue Plan funds to improve ventilation at schools

Further Reading

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.