RTT in Tennessee

Assessment Done Right

by Pam Derringer

A teacher reviews the EVAAS tests.

Mary Reel is a passionate champion of the unique statewide student assessment system that helped Tennessee become one of the first two states to win Race to the Top funds, earlier this year. Reel, who is school superintendent in the 2,100-student district of Milan, calls the Tennessee Value Added Assessment System (TVAAS) “value added on steroids,” and has used the data system to turn around struggling students, individual schools, and now a district. TVAAS so impressed the Feds that Tennessee won $502 million in Race to the Top funds; Milan will get $367,000 over the next four years.

“Nobody in leadership has been more successful with TVAAS than Mary Reel in various roles,” says former statistics professor Bill Sanders, who created the TVAAS data-assessment model with his wife, June Rivers, nearly 20 years ago.

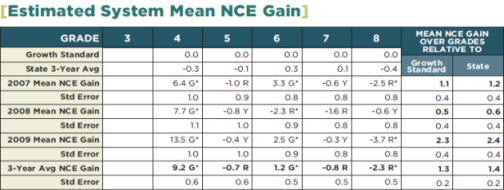

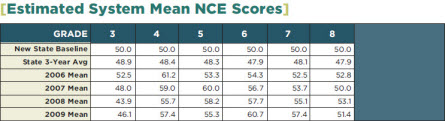

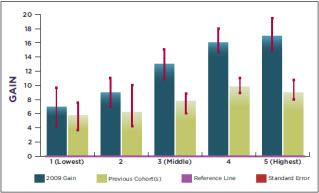

As a result of Reel’s efforts, Milan grades three through eight now have the second-highest cumulative value-added scores in the state, Sanders says. And the high school (which is falling short of the target but making Acceptable Yearly Progress) will follow, he predicts.

The TVAAS testing and administration helped Tennessee schools win Race to the Top funding. TVAAS explained

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

TVAAS is a longitudinal database that tracks individual student achievement year by year, subject by subject, teacher by teacher, based on the yearend TCAP (Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program) state achievement scores. Using the spring TCAP results, the complex TVAAS data-analysis system can predict the following fall which students will need extra help to pass the next year-end test. And because it correlates with the state curriculum, TVAAS can pinpoint the students who are failing to make adequate progress at numerous points throughout the year and even measure the effectiveness of specific teachers based on how much their students learned the previous year. “TVAAS is the greatest tool we have,” Reel says.

The beginning

Reel knew the power of the TVAAS data when she arrived in Milan three years ago, but the staff did not. She had to win the district’s teachers over. And to do so, she had to change the culture, end excuses, and expect all students to achieve.

Data was the key. After teachers were trained in how to get data themselves, they became empowered by it and began using data to experiment in the classroom and test the results. “Teachers now have direct access to pull customized reports, and they know what they are seeing,” Reel says. “They need to be mining the data all the time.”

And when the state began to impose penalties for missing NCLB targets, Milan was ready. The district already had the data tools and plans to meet the state requirements in place.

The district is easily making most of its state achievement benchmarks, scoring fourth or fifth out of 136 districts by subject, second or third in the state for elementary, and in the top quadrant for grades three through 12, Reel says. Some African-American and special-needs students are not meeting minimum state achievement levels, however, so Milan will address this gap by changing instruction and implementing daily classroom assessments where they are needed. (The district is 22 percent African-American, 16 percent special needs, and 57 percent economically disadvantaged.)

More assessment tools

Although TVAAS is Milan’s primary assessment tool, the district uses numerous others, including CompassLearning through second grade and Discovery Education and ThinkLink for third through eighth grades, administering them two or three times a year, according to Cathy Moore, assessment supervisor. If a child is not making sufficient progress on the April assessment program, Moore says, Milan can initiate intervention before the TCAP test at the end of the year. Another extremely helpful tool, Reel adds, is Dibbles, which assesses language fluency in the early grades.

The major assessment breakthrough, Moore says, is TVAAS, which, for the first time, gives the district the ability to follow an individual student’s records from one year to the next. “Teachers are more involved now,” she says. “Once TCAP comes out, they can customize a report for individual students and project where they should be to be on task.”

Last year Milan added another innovation: data boxes. Placed in the principal’s office, the data boxes contain a folder for each child receiving extra help, enabling all instructors working with a particular student to share progress updates.

The network impact

Lisa Bradford, supervisor of accountability and technology, says, Milan doesn’t usually have problems with Web-based assessments. The district had to resolve several problems with CompassLearning and Discovery last year after program upgrades, however. Milan also had to increase its bandwidth last year and started conserving network use by limiting video and audio streaming unrelated to instruction.

The spread to other states

Now available for other states through the Education Practice at SAS, the generic Education Value Added Assessment System (EVAAS) does require modification for different states and has been criticized for its complexity, according to Bill Sanders. But, he says, complexity enables the model to be far more accurate despite challenges like assessing several teachers working with the same students and inputting data for a student who has missed tests.

“You want people to trust in the diagnostic value of this, start building on what they are doing well, and address weaknesses,” Sanders says.