Old or New, Maps are Cool

I love the ability of digitized maps to allow access to all sorts of data in all sorts of very visual ways.

Can you ever have too many maps?

The obvious answer is no. You can never have too many maps.

So when I ran across some very cool old maps last Saturday at the Wichita Flea Market, there really wasn’t any question about whether or not I would buy them. The question was how many will I buy.

I settled on two. Which means my wife helped me decide that I should settle on two. There are quite a few maps already in my house and I was gently made aware of that fact. Which means semi-gently.

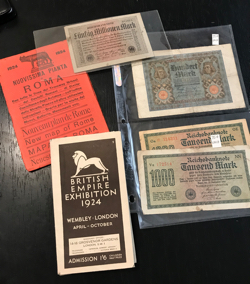

Both of the maps I walked away with are almost 100 years old. One is a 1924 map of tourist Rome published in Italian, the other a map highlighting the 1924 British Empire Exhibition with suggested mass transit options from around the London metro area. So cool.

Perfect for displaying, reading, primary source analysis, (the Empire Exhibition and its various colonial pavilions is just asking for some in-depth conversation) or just wafting in the 100 year old smell.

But while we all can agree how cool old maps are, new maps are nothing to sneeze at. I love the ability of digitized maps to allow access to all sorts of data in all sorts of very visual ways. Take a look at these two new atlases from the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond.

Tech & Learning Newsletter

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

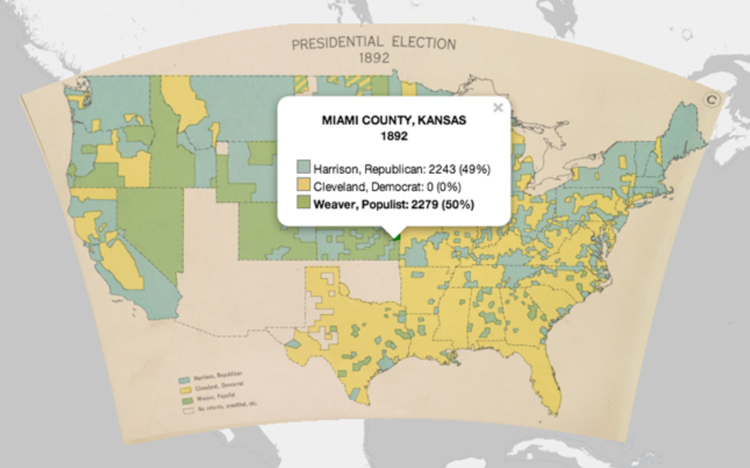

The first collection of digital maps, the Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, is based on an atlas that was original created in 1932 by Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright. Many of those beautiful maps have been enhanced:

. . . in ways impossible in print, animated to show change over time or made clickable to view the underlying data – remarkable maps produced eight decades ago with the functionality of the twenty-first century.

Like the original, there are 14 different chapters and almost 700 maps. All based on older maps but digitized and edited to make them more accessible and richer in content. And like the original, the atlas addresses a broad range of issues.

Beginning with a chapter consisting of 33 maps on the natural environment and a second containing 47 maps documenting the evolution of European and later American cartographic knowledge about North America, the atlas mapped an exhaustive number of historical topics: exploration and settlement of the continent, the location of colleges and churches, disputes over international and state boundaries, voting in presidential elections and in Congress, reforms from women’s suffrage to workmen’s compensation, transportation, industries, agriculture, commerce, the distribution of wealth, and military history.

For twenty-first-century audiences, it’s probably no surprise that it’s missing a few things as an historical atlas. Besides the fact that it’s now more than eighty years out of date, it is primarily focused on Americans of European descent – though, to be fair, it certainly contains a significant number of maps showing the geographic distribution of people of different ethnic and racial backgrounds. Yet whatever the atlas’s shortcomings, browsing through its many thoughtful and often beautiful maps one can’t help but be impressed. Anyone interested in American history before 1930 is almost certain to find many maps in the atlas that are both interesting and useful.

So if you’re teaching any US history, the newly updated digital version is a no-brainer. Head to the About page to jump start your time in the Altas.

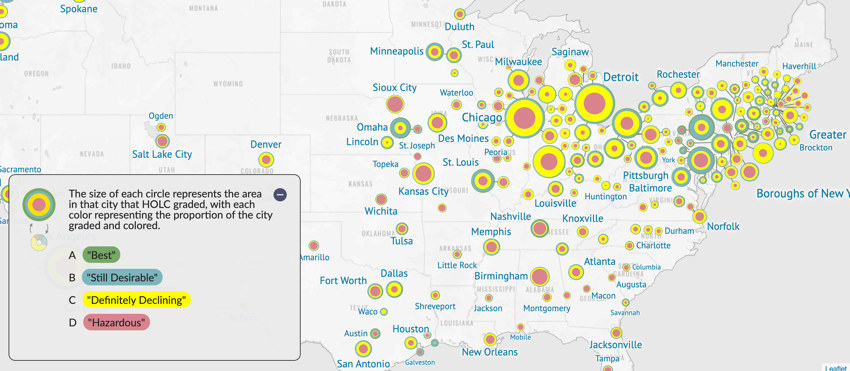

But wait. There’s more the people at Digital Scholarship Lab weren’t finished. They’ve also created American Panorama, an historical atlas of the United States for the twenty-first century. “It combines cutting-edge research with innovative interactive mapping techniques, designed to appeal to anyone with an interest in American history or a love of maps.”

So . . . I’m listening.

It’s a smaller collection of just eight maps so far but the maps move closer to the present, with one map focusing on electing the House of Representatives from 1840 – 2016 and another on America’s foreign-born population up to 2010, for example.

But all of the maps give you tools to help kids actually see history and begin to make sense of events in ways that simple text cannot. The Mapping Inequality map that highlights the redlining of home loans by the Home Owners Loan Corporation during the 1930s and 40s is a powerful way to jumpstart and deepen a conversation around civil rights and racism in the US.

Used together, these two updated versions of cool old maps like the ones I uncovered at the flea market give you powerful tools to hang on your teaching tool belt.

(And don’t forget to use the Library of Congress and National Archives map analysis worksheets to help kids unpack all the goodness.)

cross posted at glennwiebe.org

Glenn Wiebe is an education and technology consultant with 15 years' experience teaching history and social studies. He is a curriculum consultant for ESSDACK, an educational service center in Hutchinson, Kansas, blogs frequently at History Tech and maintains Social Studies Central, a repository of resources targeted at K-12 educators. Visit glennwiebe.org to learn more about his speaking and presentation on education technology, innovative instruction and social studies.