Making Data Meaningful With FH Grows

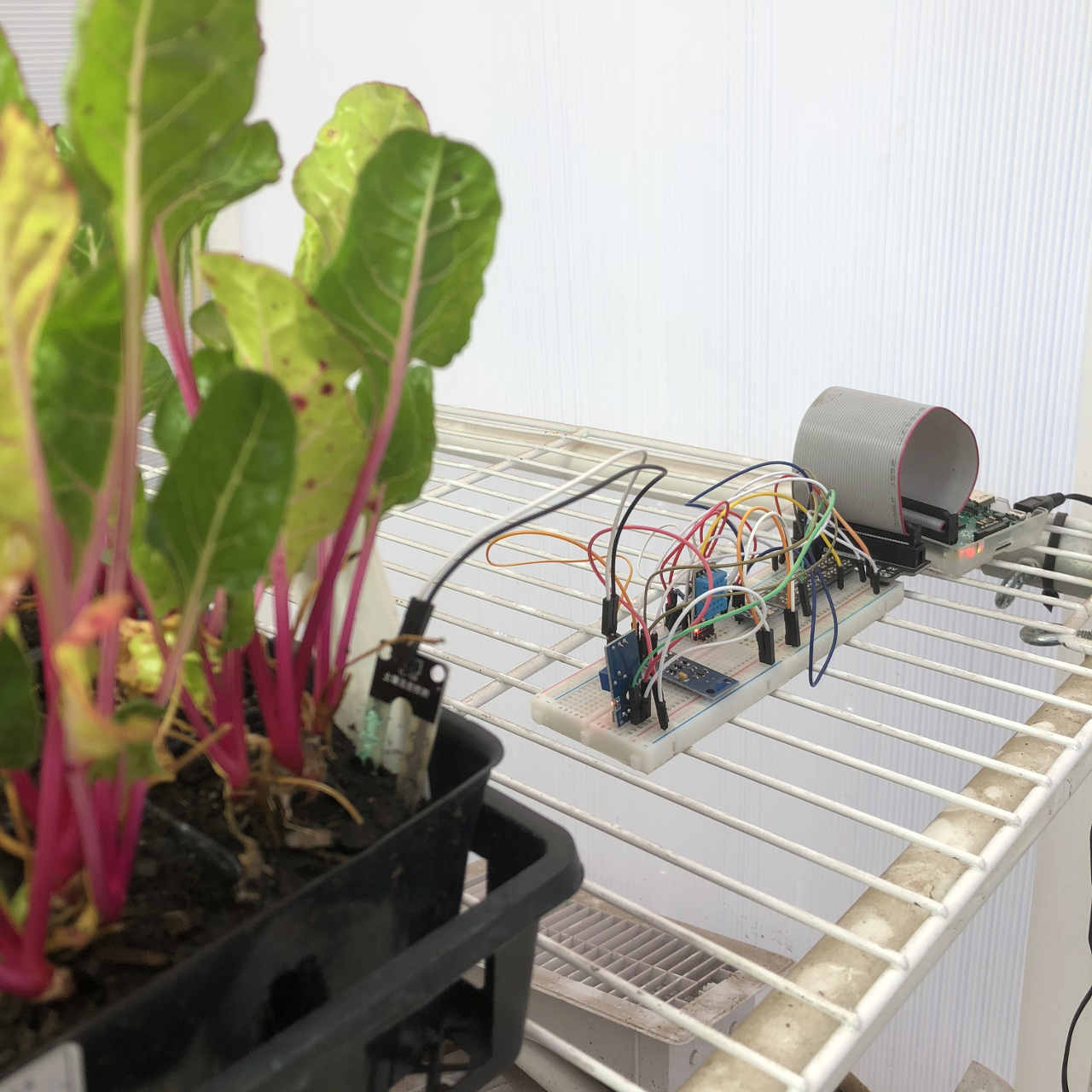

To get the most out of our school gardens, students have built sensors and monitors using Raspberry Pis.

We have never collected more data about our students and society in general. The problem is most people and institutions do a poor job interpreting data and using it to make meaningful change. This problem was something I wanted to tackle in FH Grows.

FH Grows is the name of my seventh grade class in Fair Haven Innovates. FH Grows is a student-run agriculture business at Knollwood middle school in Fair Haven, New Jersey. In FH Grows, we sell our produce to community members and restaurants online and through our student-run farmers markets. Any produce we do not sell we donate to our local soup kitchen. To get the most out of our school gardens, students have built sensors and monitors using Raspberry Pis. These sensors collect meaningful data about our gardens which we can interpret and then turn our data into action.

Turning Data into Action

In the greenhouse, our gardens, and alternative growing stations (hydroponics, aquaponics, areoponics) we have sensors that log the temperature, humidity, and other important data points that we want to know about our garden. This data is then streamed in real time, online at FHGrows.com (I’ll also embed the dashboard at the end of this post). When students come into the classroom one of the first things we look at is the current, live data on the site and find out what is going on in our gardens. Over the course of the semester, students are taught about the ideal growing conditions of our garden. When looking at the data, if we see that the conditions in our gardens aren’t ideal, we solve the problem.

If we see that the greenhouse is too hot, over 85 degrees, students will go and open the greenhouse door. We recheck the temperature a little bit later and if it is still too hot, students will go turn on a fan. But how many fans do they turn on? After experimenting, we know that each fan lowers the greenhouse temperature between 7-10 degrees. Opening the door and turning on both fans can bring a greenhouse than can push close to a 100 degrees in late May or early June down to a more ideal 70-80 degrees.

Turning data into action can allow for some creativity as well. Over-watering plants can be a real problem for students. After some research, we found that our plants were turning yellow because we were watering them every day instead of just when they needed it. How could we solve this problem and become more efficient at watering? Students built a Raspberry Pi that used a moisture sensor to find out when a plant needed to be watered. We used a plant with a moisture sensor in the soil as our control plant. We figured that if we watered the control plant at the same time we watered all our other plants, when the control plant was dry (gave a negative moisture signal) the rest of the plants in the greenhouse would probably need to be watered as well.

This method of determining when to water our plants worked well. We rarely ever saw our plants turn yellow from overwatering. Here is where the creativity came in: since we received a signal from the Raspberry Pi when the soil was dry, we played around with what we trigger with that signal. We displayed the moisture data on the dashboard along with our other data, but we also decided to make the signal trigger an email. When I showed students how they could write anything in the body of the email from “the plant,” they decided to write the email message from the plant in first person. Every week or so, we received an email from Carl the Control Plant asking us to come out and water him and his plant friends! We later sold this moisture sensor with an email trigger as a product for our customers who forgot to water their plants at home.

If students don’t honor Carl the Control Plant’s request for water, use data to know when to cool our greenhouse, or take similar actions to protect our plants based on the data they collect can have devastating consequences. It doesn’t take long for a hot greenhouse or lack of water to kill our produce. This is a lesson that is unique to combining data literacy with a school garden: failure to interpret data then act based on their interpretation has real consequences. Or, as I explain it to students, not making a decision is making a decision. When it takes 60-120 days to grow the average vegetable, the loss of plants is a significant event for our program. We lose all the time and energy that went into growing those plants as well as lose all the revenue they would have brought in for us. I love the urgency that combining data and the school garden creates because many students have learned that is better to act on an educated guess than to not act at all.

Tech & Learning Newsletter

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Using Data to Spot Trends and Make Predictions

The other major way we use data in FH Grows is to spot trends and make predictions. Different than using data to create the ideal growing conditions in our garden everyday, the sensors that we use also provide a way for us to use information about the past to predict the future.

FH Grows has about two years’ worth of weather data from our Raspberry Pi weather station. Using weather data year over year, we can start to determine important events like when it is best to plant our veggies in our garden.

For example, one of the most useful data points on the Raspberry Pi weather station comes from the ground temperature sensor. Last semester, we wanted to squeeze in a cool weather grow in our garden. This post-winter grow can be done between March and June if you time it right. Getting an extra growing cycle from our garden is incredibly valuable not only to FH Grows as business (since we would be growing more produce to turn around and sell) but as a way to get an additional learning cycle out of the garden.

So using two seasons worth of ground temperature data, we set out to predict when the ground in our garden would be cool enough to do this cool veggie grow. Students looked at the data we had from our weather station and compared it to different websites that predicted the last frost of the season in our area. We found that the ground right outside our classroom warmed up two weeks earlier than the more general prediction given by websites (probably because it is a protected courtyard, kids guessed). With this information we were able to get a full cool crop grow at a time where our garden used to lay dormant. We will be doing the same this fall to try and get another cool veggie grow before the first frost of the season. Two more growing seasons from our garden thanks to data!

We also used our Raspberry Pi to help us predict whether or not it was going to rain over the weekend. Using a Raspberry Pi connect to Weather Underground and previous years’ data, if we believed it would not rain over the weekend we would water our gardens on Friday. If it looked like rain over the weekend, we let Mother Nature water our garden for us. Our prediction using the Pi and previous data was more accurate for our immediate area than compared to the more general weather reports you would get on the radio or an app, since those considered a much larger area when making their prediction.

It seems like we are going to be collecting even more data in the future, not less. It is important that we get our students comfortable working with data. The school garden supported by Raspberry Pi’s amazing ability to collect data is a boon for any teacher who wants to help students learn how to interpret data and turn it into action, a skill that will be in demand as we continue to collect massive amounts of data just waiting to be interpreted.

Until Next Time,

GLHF

cross-posted at Teched Up Teacher

Chris Aviles presents on education topics including gamification, technology integration, BYOD, blended learning, and the flipped classroom. Read more at Teched Up Teacher.