E-Rate Update

A real-time roundup of recent promises and practicalities for the county’s largest edTech initiative and what it may mean for your school district.

FCC COMMISSIONER JESSICA ROSENWORCEL REMARKS @ SXSWEDU CONFERENCE & FESTIVAL

AUSTIN, TEXAS , MARCH 6, 2014

My children are not going to know the fine art of clapping together erasers. For me, that purple ink and the physical crank of the mimeograph machine was a practical cap on copying and sharing information. But for my kids, all they will know is the infinite capacity of digital distribution. And content for them will mean a lot more than just the printed page or a dusty set of school film reels. Educational texts are being remade and rethought as tablets change the ways we access all forms of media and information.

In short, broadband and connected devices are changing every aspect of our lives. We live in an age of always-on connectivity. Increased broadband capacity and decreased costs of cloud computing are changing the ways we access and create content. So many of our social spaces are virtual. And mobility means we can take the content we consume and create with us wherever we go.

In fact, from my perch at the FCC I can now tell you we are now a nation with more mobile phones than people. One in three adults has a tablet computer—and that number is growing fast.

But the most stunning changes are happening with school-aged kids. Three-quarters of all children now have access to a mobile device like a smartphone or a tablet. Seventy-two percent of children under age eight have used these devices for some kind of media activity. Almost one in five now do so on a daily basis. Among teenagers, half own their own smartphones. Nine in ten have used social media and 95% use the Internet regularly.

We are kidding ourselves if we believe all this change stops at the school doors. It will not. So if we are smart, we will let it in and wrestle with its real potential—and do good things. Because doing anything else will not prepare our students for the world they live in. Already, 50% of jobs today require some digital skills. By the end of the decade, that number is going to be 77%. We do our students no favors when we strand our schools and classrooms in the industrial era. After all, we live in the digital age.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Other nations recognize this. Countries around the world are wiring their schools with high-speed broadband. In South Korea, 100% of schools are schools are connected to high-speed broadband and schools are converting to digital textbooks by 2016. Ireland will have all schools connected to 100 megabits this year. Finland will have all schools connected to 100 megabits next year. Meanwhile, in both Turkey and Thailand the government is seeking a vendor to supply tablet computers to millions of students for a new era of digital learning.

There is no reason for us to settle for the status quo. There is no reason for us to let other nations take the lead. We can do this. We can make sure that all American students have access to high-speed broadband no matter who they are, where they live, or where they go to school.

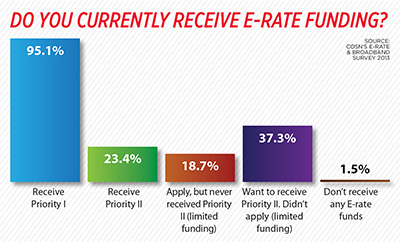

Now, I want to leave behind the lofty and get into the details. I want to talk about the mechanics of E-Rate. E-Rate, as I mentioned at the outset, is run by the FCC and is the nation’s largest education technology program. It helps connect all of our schools and libraries to modern communications and the Internet. E-Rate support is based on need. More funding is available for those schools and libraries serving students in low-income and rural areas.

E-Rate is the byproduct of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Now think back to 1996. Big broadband was in its infancy. Dial-up was our online destiny. And everyone here probably called the Internet the information superhighway. I know I did. It was a long time ago.

Back in 1996 only 14% of schools had access to the Internet. Today, thanks to the support of the E-Rate program, more than 95%of schools are now connected. That might sound like the E-Rate job is done. But nothing could be further from the truth. Because the challenge today is not connection—it’s capacity.

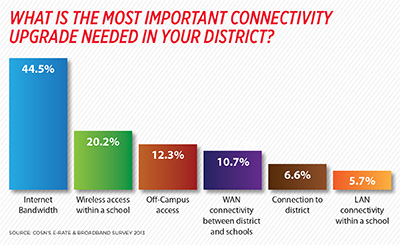

Too many of our schools that rely on E-Rate access the Internet at speeds as low as 3 megabits. That is lower than the speed of the average American home. But in many cases, those schools have 200 times as many users!

Think about what that means. It means too many schools do not have the capacity to offer high-definition streaming video. It means too many schools are unable to take advantage of the most innovative digital teaching tools. It means too many students will lack the ability to develop the science, technology, engineering, and math— or STEM skills—that we know are so essential to compete.

But there is good news. We are doing something about it. At the FCC we recently started a reform effort to modernize our E-Rate system—what I like to call E-Rate 2.0. Just like with the evolution of any operating system, we need to take the good that we have put in place, build on it, and upgrade it for the future.

At the FCC, this means we have a public rulemaking. Last summer we proposed changes to E-Rate and asked for ideas from stakeholders of every stripe. Right now we are processing all of these ideas. There are a lot, so it is taking some time. But when we finish, we need to take this program that Congress authorized almost two decades ago and get it in good shape for the broadband era. If we just keep on keeping on with the E-Rate program we have, we will miss a big opportunity—the opportunity to bring digital age learning to all of our schools.

I think we can do it, so let me talk about how. You are probably familiar with the three R’s: Reading, ‘Riting, and ‘Rithmitic. So let me move on down the line and introduce you to the three S’s of E-Rate reform: Speed, Simplify, and Spending Smart. Or maybe that’s four. Then again, the three R’s were never all R’s. So I think I can take some liberties. But that aside, I want to talk about the three things we need to focus on if we want to put E-Rate 2.0 in place.

First, Speed. If you are a school and want to run the most up-to-date educational software, you need high-speed, high-capacity broadband. But a survey from Project Tomorrow found that only 15% of schools believe they have the bandwidth they need for instructional purposes. That is a problem—because we have moved from a world where a connected computer lab down the hall is a nice-to-have to a world where high-speed broadband to the classroom is a need-to-have.

So let me tell you what I mean by really high-speed broadband. In the near term, we want to have 100 megabits per 1,000 students to all of our schools. By the end of the decade, we want to have 1 gigabit per 1,000 students to all of our schools.

I call these goals dream likely and then dream big. I think we can do it. And more than that, I think that if we adopt these capacity goals we will send a strong signal to educational markets. Because by making more bandwidth available at nationwide scale we can foster new opportunities for creative content, services, teaching tools, and devices—everywhere.

Plus, the spillover effect from bringing broadband to anchor institutions like schools is huge. Because simply bringing these kinds of speeds to schools makes it incrementally less expensive to deploy higher speed broadband to the homes and businesses nearby.

To meet these goals, we are going to have to do things differently. That means the FCC needs to collect better data from each of our applicants about what capacity they have and what capacity they need. That way we can fine tune our efforts over time to achieve our goals.

Second, Simplify. The E-Rate program is too complicated. This is a program that can be about blazing a path for broadband in the digital age. Then why does it have such a long and messy paper trail? It has become too difficult and expensive for schools to navigate our process, especially the low-income and rural schools that are most in need. That is just not right.

So I want us to reduce the bureaucracy associated with E-Rate. To this end, I would like to see multiyear applications. As small as that sounds, the impact could be big. If applications were due every other year, that would cut the administrative cost of applying in half.

I also would like to see more incentives for consortia in the application process. When schools work together they can navigate the process together and benefit from more cost-effective bulk purchasing. Moreover, by encouraging consortia to include nearby schools and districts that lack high-speed connections, we can use local forces to help bring everyone along. That respects the local tradition of education in this country—but also helps us reach our national goal: getting 99% of students connected to high-speed broadband over the next five years. I think we can do it. And I think greater use of consortia is the ticket.

A simpler process also should mean greater transparency during the review process for E-Rate applicants. Critics have charged that our existing process is a bit opaque—and they are right. Beyond that, we should welcome other ideas from E-Rate applicants that can simplify the process and reduce the bureaucracy of this program.

The last S—or two—is Spending Smart. We need to spend our limited E-Rate dollars intelligently. Spending smart means better accounting practices that the FCC has already identified will free up for more E-Rate broadband support over the next two years.

But spending smart goes beyond that. Because on a long-term basis we need to make sure that all E-Rate support is focused on high-speed broadband. To that end, the time has come to phase down the estimated $600 million this program now spends annually on outdated services like paging. If we reduce this expense over time, we can free up more funds for high-capacity services.

Spending smart also means owning up to the fact that inflation has cut the purchasing power of this program. The E-Rate program was sized at $2.25 billion in annual support back in 1998. That was when .03% of American households had Internet access at any speed above dial-up. That was when gas was just over a dollar a gallon. It was a long time ago.

We need to fix this now. At a minimum, we need to restore the purchasing power of this program by bringing back what inflation has taken away. Between when the cap was put in place and other adjustments were made in 2010 that is nearly $1 billion. But we should go beyond this and identify what more we need to meet the goal of connecting 99% of schools in five years. Because when it comes to bringing broadband to schools, the rest of the world is on course to do this. We can let them out spend us, out educate us, and out achieve us. Or we can be courageous—and do something about it now.

One further thought—about equity and opportunity. Beyond the S’s of speed, simplify, and spending smart. I think a reformed E-Rate speaks to essential issues of equity and access in education. Today, three out of ten households do not have broadband access. Think about what it means to be a student in one of those households—typically low-income and often rural. It means just getting homework done is hard. It means applying for a scholarship is challenging. By bringing broadband to all of our schools, we will be making digital age opportunities available for all. That matters.

So there you have it. E-Rate is a program that has done a lot of good. But we can do so much more. With a reformed E-Rate—or E-Rate 2.0— we can extend the reach of broadband in our schools. We can expand the range of educational content. We can harness digital and mobile platforms and teach in new and exciting ways. In short, we can seize the good in new technology and prepare all of our children for success in the 21st century. And as a policymaker—and a parent—I think that is something worth fighting for.

U.S. SEN. RON JOHNSON (R-WIS.), MEMBER OF THE SENATE COMMERCE, SCIENCE AND TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE.

OPINION PIECE ORIGINALLY PRINTED IN MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL, FEBRUARY 21st, 2014

Based on how much we spend, every child in America should be getting a world-class education, which would include connecting our classrooms to digital opportunities. To get there, the federal government doesn’t need to spend more money — the Federal Communications Commission already runs a program called E-Rate that distributes over $2 billion to schools and libraries to purchase communications services each year.

What we do need is real reform in Washington and an end to the waste, fraud, and abuse inherent in the current program.

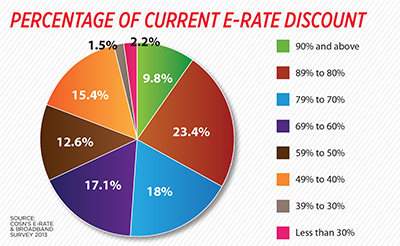

Here’s how E-Rate works today: Each year, schools and libraries purchase communications services from an FCC-approved list. If the FCC favors a particular service, the school gets a subsidy (or “discount”) of up to 90% of the cost of service — with no hard cap. In contrast, most schools won’t receive any discount for less-favored services. The funds for these subsidies come out of the pockets of all Americans via the Universal Service Fund charge on their monthly phone bills.

To put it kindly, today’s E-Rate program has some problems. For one, schools have every incentive to gold-plate their networks since the more they spend, the more E-Rate pays. Consider the $73 million the Atlanta public school system got from E-Rate to build an optical fiber network between its schools. Some of that money wired up schools just before they were shut down. Millions were spent on a wireless network before that project was abandoned. Maintaining the network cost millions of dollars, and even after it was built, most students had less than one hour per day of computer use.

Similarly, the discount system is so generous that some schools have little skin in the game, encouraging them to buy services unrelated to student needs. So some schools might give their administrators BlackBerries and use E-Rate funding to pay for wireless phone service, text messaging, voice mail, and data. Others might upgrade the bandwidth available to non-instructional buildings such as athletic facilities and bus depots.

The priority system further distorts the marketplace. For example, if a rural school wants to connect its students’ laptops and tablets in the classroom, it either can buy cellular data connections for each of its students or it can buy cost-effective Wi-Fi routers. But the priority system puts a thumb on the wrong side of the scale: E-Rate likely will cover up to 90% of the costs of the more expensive cellular service but won’t pay a dime for the routers. That doesn’t make any sense.

And it gets worse. The E-Rate program is supposed to be about connecting kids to next-generation technologies, but it still prioritizes basic telephone service — to the tune of half a billion dollars per year. Indeed, a school can get funding for paging service (remember pagers?) and international long distance more easily than it can get money to wire up a classroom. That makes no sense.

Instead of throwing more money at the problem, we should turn the current E-Rate program into a fiscally responsible one that puts kids and common sense first.

We should end the incentive to spend more to get more by allocating E-Rate’s limited dollars on a more equitable per-student basis, with higher allocations for schools serving rural and low-income students. And let’s replace the discount system with a more responsible matching requirement: Every school should be required to match a higher percentage of the E-Rate dollars it gets. With common-sense reforms like these, schools will be more prudent about how they spend E-Rate funds than they are now.

A student-centered program also means ending the subsidies for telephone service and other services unrelated to student learning. It means ending the skewed system of prioritizing services and giving local officials the flexibility to spend their E-Rate budget more efficiently. And it means having a high-ranking school official, like a principal, certify that E-Rate funds will be used to benefit students.

Real reform also means empowering parents to check up on what schools are doing with E-Rate funding. Schools and service providers should disclose more clearly and in detail exactly what students are getting with federal funds. All of this information should be collected and made available on a single website that would allow any American to see with specificity how any school in the nation has spent its E-Rate money.

A student-centered E-Rate program would end the abuse of the program and make sure that the money each of us contributes to E-Rate actually focuses on students. Real reform would connect children throughout Wisconsin with next-generation opportunities—and we are working to make that promise a reality.