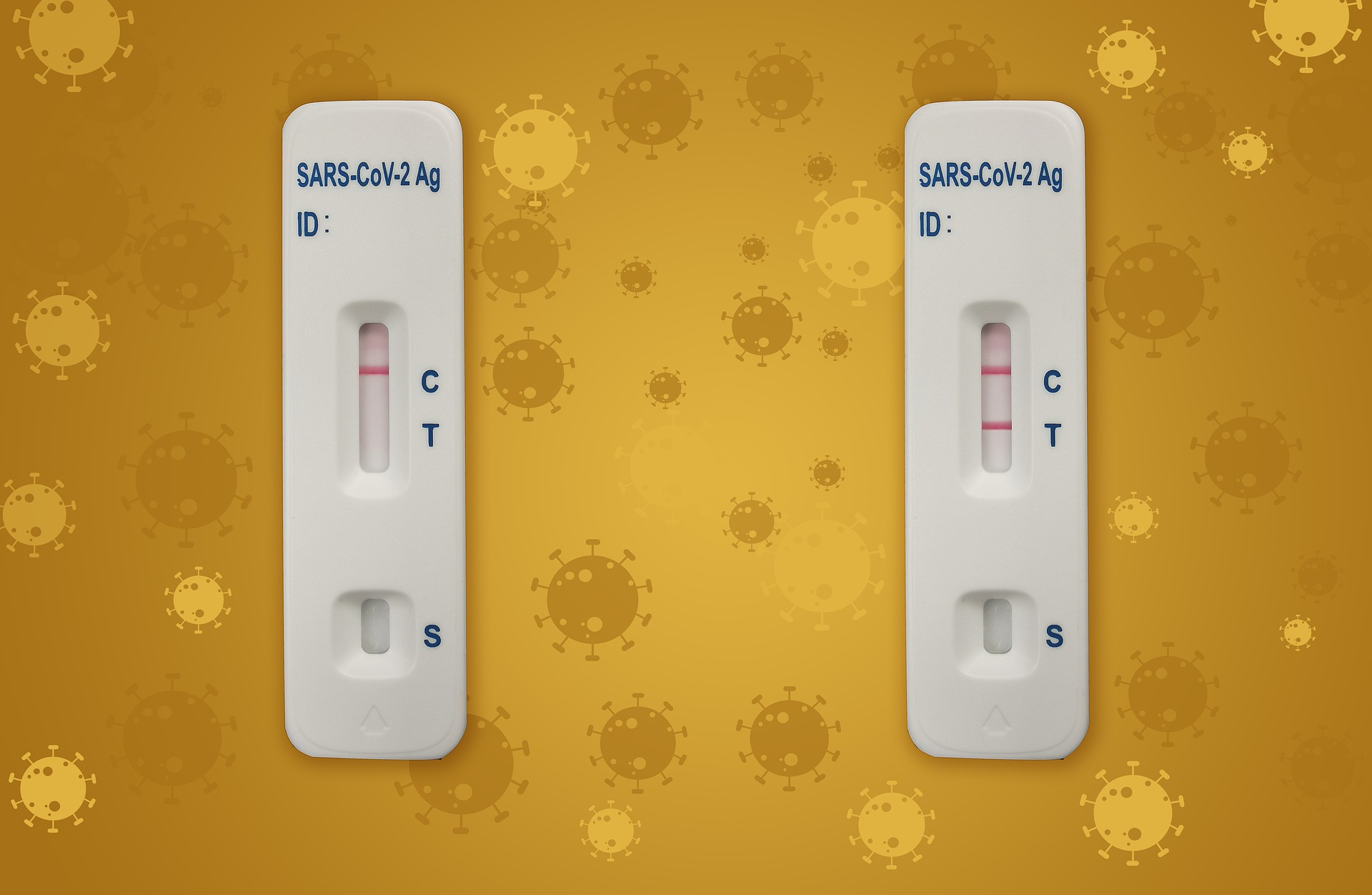

Do Rapid Antigen Tests in School Testing Programs Work in Detecting Omicron?

A recent study of rapid tests suggests these products are often not catching positive Omicron cases before becoming infectious. What does that mean for schools?

The rapid antigen COVID tests that are a part of many districts’ virus testing strategies do not appear to be working as well against the Omicron variant of the virus.

A recent study looked at 30 people who caught COVID in December, worked in businesses in New York and San Francisco, and were being tested daily by both PCR tests and antigen tests.

The study found that following a positive PCR test on Days 0 and 1, all rapid antigen tests produced false-negative results, even though in 28 of the 30 cases, the viral load detected was high enough to spread the virus to other people. In four of the cases, researchers were able to confirm that infected people transmitted the virus to other people before testing positive on a rapid antigen test.

“Despite having incredibly high viral loads in their saliva, they were failing to be detected by antigen tests,” says Anne Wyllie, PhD, a co-author of the study and researcher at the Yale School of Public Health.

Wyllie, who previously led a team at Yale that developed a saliva-based PCR covid test, says that although the study was small, there have also been many anecdotal reports during the Omicron surge of people getting false-negative results from the antigen test.

The implications of this for schools and other institutions that rely on antigen tests are significant. “The results that you are getting from a nasal-based antigen test might not be accurately reflecting your infection status,” Wyllie says. “If people have had a high-risk exposure, or if they have typical symptoms, especially of Omicron, they really need to pay attention to their exposure, and even if they get a negative antigen test result, they can't rely on that.”

Instead, Wyllie suggests retesting with an antigen test a day or two later, or getting a PCR test. In a school setting, this might mean assuming students who have had high-risk exposures could be contagious with COVID in the meantime.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Should Rapid Tests Be Used Differently?

Another recent study of the Abbott BinaxNOW test found that specific antigen test was as good at detecting Omicron as previous variants. However, the study was not designed to address when the virus appeared in the nose and therefore at what stage in a person’s illness the test would be effective.

“If you take the virus and you put it on an antigen test, yeah it works,” Wyllie says. The problem, however, is that with an Omicron infection the virus is often not present in the nose soon enough to be detected in the early days of infection.

COVID infections appear to be present earlier in saliva than in the nose, particularly with Omicron, which has led some to suggest those using rapid tests should swab their throat in addition to their nose.

“There are other tests internationally, which have been successfully validated for oral swabs,” Wyllie says. “We have seen many individuals in the general public who have been hacking the current antigen test and including an oral swab. So I think there should be pressure on the manufacturers to actually validate this. And if it proves successful to update the guidance so that oral [swobs] can be included, if they don't interfere with the test.”

Should the Messaging Around Rapid Tests Be Updated?

Proponents of rapid tests have touted the accuracy when it comes to measuring a person’s current level of infectiousness. Michael Mina, a doctor and epidemiologist, formerly of Harvard, has been one of the most prominent voices in public health advocating for the widespread availability and use of COVID tests, including within schools. In mid-January, he announced on Twitter that he had caught COVID himself and noted rapid tests did not turn positive until more than 12 hours after symptom onset. He believes, however, this occurred because he wasn’t contagious and wrote, “Symptoms don't = contagious virus.”

That is not what Wyllie and her co-authors found in their study, or which have been observed in many anecdotal reports around the tests. Wyllie says there has been reluctance from some public health experts to update their guidance around rapid tests given the changing disease dynamics.

“People are very set on their agenda,” she says. “I think it's actually been very dangerous for them to keep pushing this messaging.”

Are Rapid Tests Still Useful in Schools?

David Dowdy, MD, PhD, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said in an email that while not perfect, the rapid antigen tests were better than nothing. “For people who have been highly exposed, a negative rapid test should not be seen as a get-out-of-jail-free card. But for random asymptomatic screening, positive tests are likely to be true-positives – so are likely to help reduce transmission, even if they don't eliminate it,” he noted.

While a test may result in a false negative, it is much less likely to result in a false positive, Dowdy said, which means it can be helpful in school and other settings. “Antigen tests are relatively cheap, fast, and when positive can be trusted. No screening tool is perfect, but for many schools, the expense and inconvenience of testing will be much lower than the expense and inconvenience of closing entirely if transmission gets to too high a level,” Dowdy said. “I think that test-to-stay is reasonable in the midst of a major epidemic surge – since positive tests can likely be trusted. But as cases slow down, a point will come when mass testing is not needed anymore. It will be helpful for school leaders to think about what that point should be before we actually get there.”

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.