AI Is Getting Better At Grading. Should Teachers Use It To Grade?

AI grading tools can now match human accuracy and consistency in certain topics and situations putting the spotlight on the ethics of machine grading.

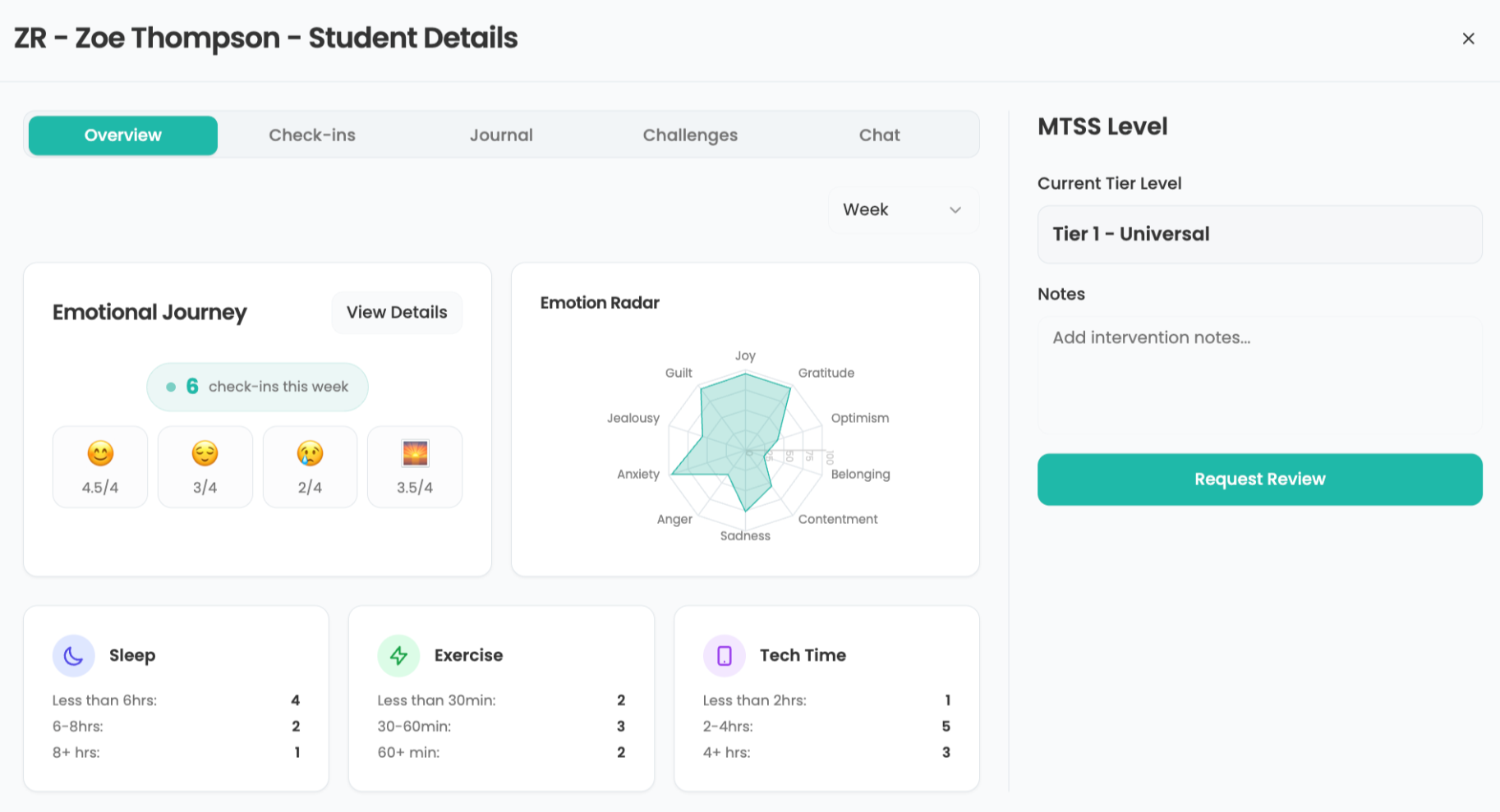

An anonymous high school teacher recently wrote to The New York Times ethicist column, asking if a teacher could ethically use AI to grade student work while actively prohibiting students' use of AI to submit their own work. To this teacher, doing so felt hypocritical.

The column’s author, Kwame Anthony Appiah, a philosophy professor at NYU, replied to the teacher that this mixed policy toward AI was ethical because the students need to practice writing while the teacher already knew how to grade. The real question, Appiah wrote, was whether AI grading tools could fairly grade students in a manner that helped them improve for the next assignment, like a skilled teacher.

As AI gets better and better, and more tools are available on the market, it’s an increasingly important question, as is a follow up: If AI tools can grade fairly and effectively, will students and teachers accept it?

AI Can Already Help With Assessments

Deirdre Quarnstrom, Vice President of Education at Microsoft, says there’s a lot of interest in the question. “As I look across the industry, I think any potential task that an educator can do, there is organizations working on how to improve that, and how to make that better,” she says.

AI is already skilled enough at summarization to help teachers in the grading and assessment process, she says, by performing initial evaluations based on a set of instructions or prompts or criteria.

Michael Klymkowsky, a biology professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, is developing an AI tool that can help assess biology students' progress. Instead of grading, it’s designed to help inform teachers on where students are at with the material. However, he says it might already be able to do a better job at grading than humans in some instances, including a mega section for a course with grading done by time-strapped graduate assistants.

“Graduate students don't always have time to grade everything equally rigorously,” Klymkowsky says. He adds that adopting a system such as this might help teachers to not be as reluctant to assign short-answer questions because of the additional time traditionally needed for grading.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Whether or not school leaders would permit such a use openly, or if students would accept its use, is another question altogether.

AI Grading Obstacles and Concerns

A recent pair of studies looking at AI assessments and writing found that AI wasn’t as good as skilled teachers, but was close and was probably better than overworked or inexperienced teachers at providing feedback.

Steve Graham, a co-author on both studies and professor at Arizona State University, says that a key to whether students and teachers become comfortable with AI-graded work are perceptions of its accuracies. “If you trust feedback from AI, then I think you're more likely to use it,” Graham says. One way to build that trust is through increased research and studies so its efficacy can be evaluated and best practices can be developed.

Still, it’s easy to imagine some teachers still being reluctant and students pushing back against poor AI-generated grades even though there is precedent for acceptance of machine-generated assessments. For example, state writing assessments are increasingly scored by computer programs less advanced than generative AI, Graham says. These tools don’t really analyze the writing, just the semantic and syntactic markers, while also assessing whether it's a match for good, quality writing.

“People were initially leery about that, but you're seeing that used more and more,” he says.

Although Graham believes AI grading and assessments overall can eventually help students learn and ease time constraints for teachers, he also stresses that we’ll need to always keep in mind the human element.

“The only reason I'd want feedback from AI is to make a paper better that I'm either writing for myself to explore something about me, or that I'm writing for other people to read,” he says. “The fear I have is that if we turn to algorithm-based feedback or feedback from ChatGPT, and we don't have other people reading our papers, well, what's the purpose here? And ultimately, we write for a purpose.”

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.