Authentic Learning: What It Is And How to Incorporate It In Your Teaching

Authentic learning is the difference between learning science and being a scientist, says educator Todd Stanley.

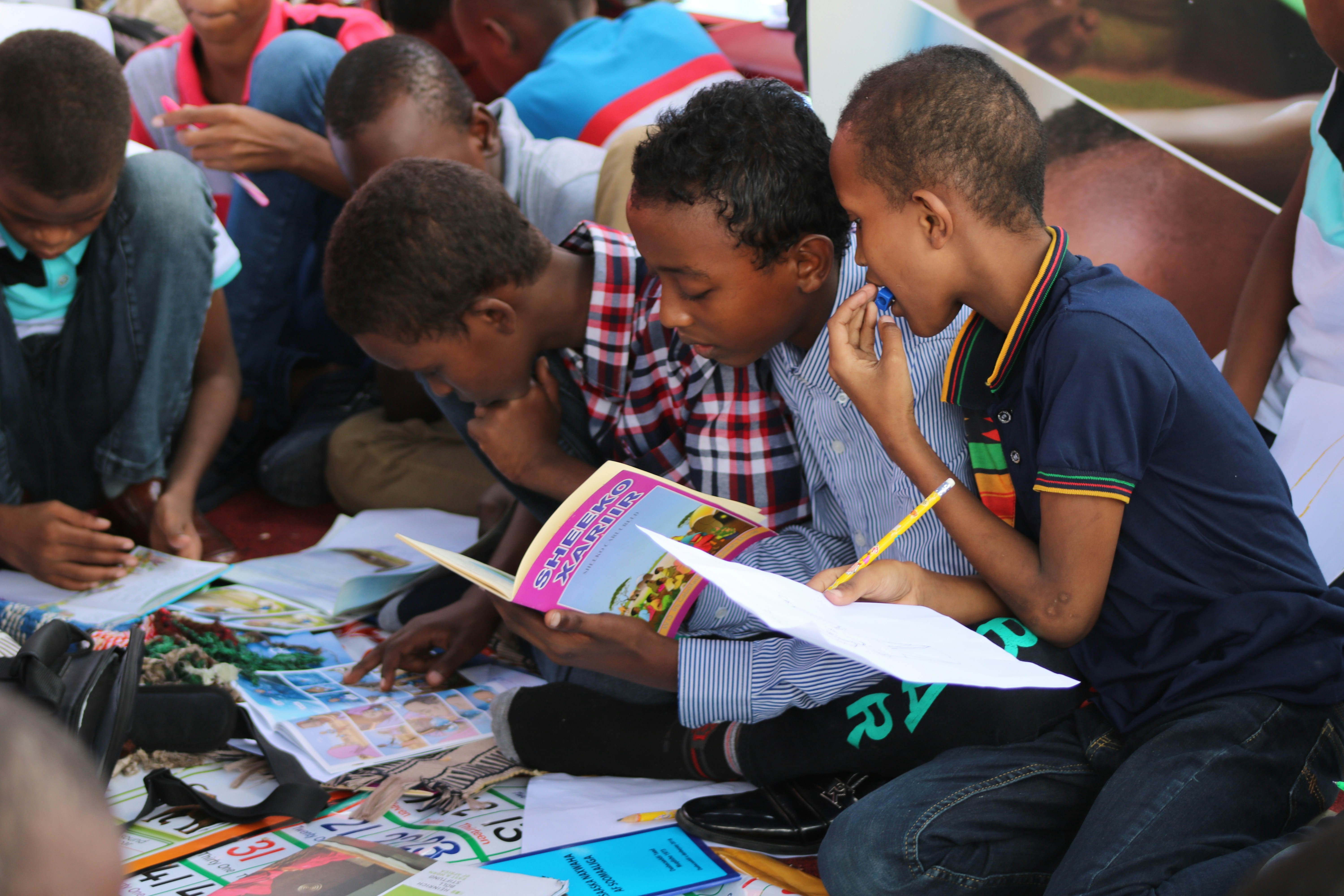

Authentic learning is a learning philosophy that puts the student in the driver's seat, encouraging them to learn through real-world experience that is authentic to them and mirrors the work professionals might do in the field. This process can deepen student learning and better prepare them for future careers, fans of authentic learning say.

“It’s the difference between reading about history and being a historian, or reading about science and being a scientist,” says Todd Stanley, an educator at Pickerington Local Schools in Ohio and author of Authentic Learning: Real-World Experiences That Build 21st-Century Skills.

Here’s everything you need to know about authentic learning from tips on how to implement it in various subjects to common misconceptions around the practice.

What is Authentic Learning?

Authentic learning often starts with the student and allows them to incorporate experiences and learning opportunities that are authentic and meaningful to them. In authentic learning classrooms, students might record a podcast about history rather than writing a history paper, and/or present various projects to authentic audiences ranging from parents to experts in the field they are studying.

The teaching philosophy is linked to approaches such as active learning, project-based learning, flipped learning, and other similar teaching practices. Stanley says that inquiry-based learning is a good catch-all for these various teaching strategies that overlap and intersect.

What Are Some Examples of Authentic Learning?

Authentic learning can involve taking a topic or unit and building a project around it that teaches students. Common examples are science projects based upon climate change in the local setting in which students attend school.

Sometimes, however, finding authentic experiences and stakes can be challenging. “I was a social studies teacher that was teaching ancient history," Stanley says. So he had to ask himself, "How do I have authentic authenticity when I'm teaching about ancient Mesopotamia?" He was able to connect the ancient world with students’ authentic experiences today by having them create a podcast about ancient Mesopotamia.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

In another class, when one of his students wanted to focus on environmental science in a manner that went beyond Stanley’s expertise, he connected the student with a leading environmental scientist and professor at a nearby university.

Stanley has also had business leaders come down for Shark Tank-style pitch events and reached out to other community experts for help with students.

What Some Misconceptions About Authentic Learning?

Stanley teaches other educators about authentic learning, and often encounters those who are worried what their principal might think and if the students will meet learning standards. He says most of the time principals love this type of innovative teaching and that meeting the standards can become easier with authentic learning — though he acknowledges there can still be a place in many classrooms for direct instruction by the teacher.

Many teachers are also afraid they don’t have the time to implement authentic learning projects in their classes. “It will take you some time at first to create the projects, but once they're created, and you're just kind of editing them, massaging them, shaping them as you go along, you find yourself having more time," he says.

What Are Some Tips For Implementing Authentic Learning?

Start small to begin, Stanley says, maybe with one unit or concept, and then build from there. Teachers should also be aware that not every project is going to go well and that’s okay. Finally, teachers should make sure to get parents on board by letting them know about how the class is working.

“You might get questions from parents who don't understand because they're going to be like, ‘This doesn't look like school when I went to school,’” Stanley says. “So I always try to be proactive with parents. I would always send newsletters home.” These would explain what the students were working on and why and how the parents could help their child with the project. “That cut off a lot of issues with parents,” Stanley says. “Because parents just want to help their kids.”

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.