COLLABORATION: AT THE ROOT OF STEM SUCCESS

When kindergarteners are collaborating to build bridges, you know the future of education is bright. Long before students in the schools and districts featured here have a chance to ask “What difference does this make?” or “When will I need to know this?” they’re out on a boat gathering samples, investigating why a family member suffers headaches, outside measuring solar energy, or making connections that lead to a career. Whether you call it STEM, STEAM, or STREAM, cross-curricular, real-world education is helping students to make a difference in their communities now and preparing them for further education and careers. And creative collaboration is the key.

KA HEI: CAPTURING THE SUN

RISING COSTS AND FEARS

“What if a tsunami hits Hawaii and cuts off our fossil fuel energy supply? We can’t even have light or running water. We’d go back to the caveman times,” says a student at Honowai Elementary School in Waipahu, Hawaii.

While clean energy and conservation issues affect us all, thanks to Ka Hei, a collaboration between the Hawaii State Department of Education, OpTerra Energy Services, and DefinedSTEM, Hawaiian students are particularly aware of the need to learn and take action to preserve their beautiful but fragile island environment. Ka Hei is “a multi-pronged approach to sustainability and incorporation of STEM,” says Brent Suyama, DOE communications specialist. Even the name is collaborative—the Hawaiian god Maui used a snare called a Ka Hei to capture the sun, and Ka Hei also means “to absorb as knowledge or skill.”

With $50 million in annual energy costs and fuel prices rapidly rising, in addition to weather changes necessitating the installation of air conditioning in schools, assistant superintendent for facilities Dann Carlson explains that the department began by investing time in writing a creative RFP to find a primary partner for this sustainability program. OpTerra won the competitive bid, which included a unique power purchase agreement financed over 20 years at a fixed rate. Finance was a particular concern, as the Hawaii legislature determines all state funding for public schools.

With DefinedSTEM as their curriculum partner, in 2014 work on the three E’s of Ka Hei—efficiency, electricity generation, and education—began. The first step was to perform energy audits in all 256 schools, install LED lightbulbs and other efficiencies, and begin educating everyone about energy and water conservation. As many schools are used as shelters during hurricanes and energy security is a pressing concern, community involvement and support are critical.

HARNESSING THE ELEMENTS

“I didn’t know we used so much fossil fuel to do … everyday stuff. We gotta do something … Now I know why so many houses have PV and why we see wind turbines. It’s all good stuff for the aina [the Hawaiian word for land],” says another Honowai Elementary student.

Ka Hei is taking advantage of the sun and wind, exploring innovative energy technology and installing photovoltaic (PV) panels. Eighty schools benefitted from a narrow window offering net energy agreements, and efforts to find creative ways to finance PV panels for the rest of the schools and to establish microgrids in five pilot schools are ongoing. This next phase, with the ultimate goal of net-zero buildings, also involves engineering storage solutions.

EDUCATION FOR EVERYONE

Ka Hei’s curricular initiatives, in partnership with DefinedSTEM, involve all 180,000 students in 256 schools across seven islands. Suyama describes the excitement of students as they monitor usage and take responsibility for their own campuses. This kind of STEM learning, he says, is tangible—and “they love it.”

The comprehensive and hands-on training for teachers includes bringing in individuals from local businesses to share their expertise as well as surveys, contests, and information to communicate to parents and guardians. Elizabeth Shigeta, curriculum coordinator for Honowai Elementary School, notes that due to this “shared training experience, teachers are able to collaborate with each other,” which creates “a more meaningful experience” for students. Sharing at home what’s learned in the classroom, she says, is “critical.”

The STEM curriculum for the initiative “connects age-appropriate information and standards,” Shigeta says, but what’s most valuable for learning is the pairing of curriculum and equipment so that it’s effective for students’ different learning modalities. As a result, even young students demonstrate a deep understanding of their connection and responsibility to their environment. “Living on an island has many good things for us to do, like go to the beach, swimming, and hiking. But we need to look at energy like we look at our island. We need to understand and care for it,” says another of Shigeta’s students.

Another Honowai Elementary student perhaps sums it up best: “Yeah. I waste a lot of energy. I know what I can do and I’m going to do it!”

Learn more about this exciting initiative at http://www.hawaiipublicschools.org/ConnectWithUs/Organization/SchoolFacilities/Pages/Ka-Hei.aspx.

TOOLS THEY USE

HONOWAI ELEMENTARY

► DefinedSTEM

► iPads

► Island Energy Inquiry curriculum and equipment (a subsidiary project of Ka Hei/OpTerra)

► LEGO MINDSTORMS

► MacBooks

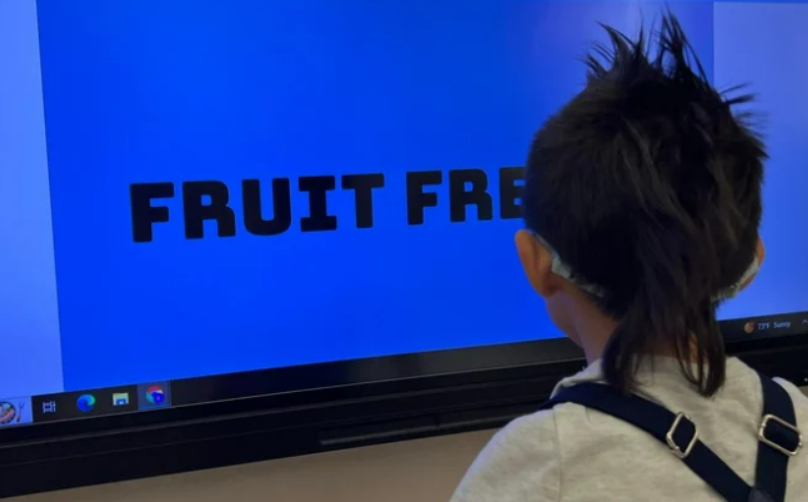

► Promethean and Smart Boards

BUILDING BRIDGES: WITH BOOKS, COURAGE, AND RELATIONSHIPS

It’s impossible to talk with Jamie Ewing, new STEM Educator at Amidon-Bowen Elementary School, in DC Public Schools, without catching the vision for STEM integration. “Most technology at the elementary level has been supplemental, as opposed to being integrated,” he says. But STEM education is all about critical thinking, and the earlier students begin learning this way, the better.

Ewing was hired to integrate STEM in third through fifth grades, but his question was: “Why not younger?” And he chuckles as he admits it’s been a learning process. When he gave Pre-K three-year-olds a pile of books to build an arched bridge connecting two chairs a few feet apart, he figured he’d need to show them how first. But the kindergarteners not only accomplished this task without being shown how but also found multiple ways to do it. Encouraging collaboration and teaching problem-solving skills at this tender age is not only possible, but critical. “By the time they reach fifth grade, this way of thinking is ingrained,” Ewing says.

Ewing brings a fine arts degree, a career in clothing design, and a dizzying array of accolades—including Microsoft Innovative Educator Expert and 2013 National Academy of Arts and Science in Education Innovator of the Year—to this school in the transitional Southwest Waterfront neighborhood of DC. Although the school has struggled and nearly all 340 students are eligible for free or reduced lunch, Ewing is impressed with the community support to create a STEM-focused school and grateful for a grant that enabled him to outfit his classroom with lots of cool tools. It’s a big transition for everyone, and Ewing is at work in these early days building relationships in the school and the community. The PD he’s doing with teachers is equal parts instruction, support, inspiration, and helping them to see how “they’re doing pieces of it already.”

Ewing is a huge fan of Scratch and uses it especially with fourth graders, teaching coding and programming. His fifth graders use littleBits which, he says, “I absolutely adore. You set up the problem and there are a hundred different ways to do it.” Makers Empire, a 3D printing curriculum, is another key tool he uses to teach problem-solving.

COMMUNITY COLLABORATION: JUST TALK TO PEOPLE

But Ewing hastens to point out that effective STEM education doesn’t require expensive equipment. His students in Seattle created instruments out of recycled materials, recorded music, and partnered with the MOHAI to present their pieces in the museum’s atrium. This kind of collaboration is not only creative, engaging, and effective—it’s also free. Ewing has found that museums and businesses often want to partner with education but don’t know how, and teachers don’t realize that they can reach out to these organizations. The solution? Talk to people. “I have yet to find someone who’s said no,” Ewing says.

Social media can also facilitate unique collaborations. One of Ewing’s classes created stop-motion videos with students in Germany, and another Skyped with a school in Detroit. Edmodo, he notes, is great for global collaboration. And Twitter is one of his favorite ways to connect, support, and share ideas with like-minded teachers everywhere (@mrewingteach).

SHIFTING MIND-SETS

Part of the challenge at Amidon-Bowen, where the only tech most students have at home is a phone, is to help them feel comfortable with it. And typing on keyboards, which Ewing (who used a typewriter in college) likens to cursive, doesn’t help. “The Surface RT with an Xbox One controller with keyboard,” he says, would be “the best tool to replace the keyboard for 21st-century kids.” It’s a struggle not to “put our mentality on something that doesn’t make sense to a ten-year-old.”

With technology and in other areas, Ewing encourages teachers to take risks and to push students to fail so they can succeed in new ways. Above all, he says, “Don’t be afraid to let students teach you. If you can get into the headspace where you don’t have to be in control, the kids can do so much more.” While it can be more work up front, and it might look crazy, “once it starts happening, and students take ownership,” Ewing says, “step back and watch it. It’s beautiful.”

TOOLS THEY USE

AMIDON-BOWEN

► Blend Space

► Class Craft

► Edmodo

► littleBits

► Maker Empire

► MinecraftEdu

► MSFT Sway

► One Note

► Scratch

► Skype

► Surface RT with an Xbox One controller with keyboard

► Touch Develop

► Twitter

SAVING LIVES AND PREVENTING HEADACHES

Many of Nancy Foote’s students have followed the STEM path from her classroom at Sossaman Middle School in the Higley Unified (AZ) School District into related careers. These include “the young lady who hated science and math but loved the tech end of it” who is now majoring in physics and astronomy at college, “the academically talented student who is working on Orphan Diseases with the White House,” a few doctors, and even one “who really is a rocket scientist.” While Sossaman doesn’t have an official STEM program, the school offers many STEM classes and has a strong robotics program.

Even in eighth grade, Foote’s students are solving real-world problems. One student, who was concerned about his dad’s headaches that baffled even the doctors, had an “aha!” moment while designing a dream house with CO monitors. His dad drove a convertible, in heavy traffic, every day. So, Foote says, “He borrowed my portable CO monitor … They set up an experiment.” Sure enough, when the car’s roof was down in heavy traffic, CO levels were “excessive,” but “with either the roof up or with light traffic, the levels were acceptable.” This discovery had a huge impact on the student’s entire family.

While we know that too many children and animals die in hot cars, without a wireless temperature probe it’s difficult to quantify how quickly a car gets too hot. Foote says, “One of my students was having a heated discussion with his mom about her leaving their dog in the car. He said it got too hot for the dog, but she disagreed. She claimed that when it was only 90 degrees out, cracking the car windows was enough.” The student borrowed a PASCO wireless temperature probe and “found that the temperature inside the car reached over 110 degrees in less than 10 minutes with the windows closed. With the windows slightly open, it took 12 minutes to get to 110. Mom decided he was right.”

Students at Sossaman engage in many exciting projects, including a thermal ice house challenge using a University of Arizona curriculum, an introduction to the engineering design process, and much more.

FOUR INGREDIENTS FOR SUCCESS

This kind of successful STEM integration grows out of a learning environment rich with certain key characteristics:

Time. Teachers, within and between schools, need time to work together, Foote says, and to “tap into the natural synergy that exists between educators.” Time for professional learning is also important. In Arizona, for example, established summer programs allow teachers to “work side-by-side with professions in STEM areas and get paid very well.”

People. Foote, who was an industrial chemist, has colleagues who bring a wealth of experience from “past lives” as a banker, a police officer, an artist, and even a dolphin trainer, to their classrooms. Foote notes that retirees “are also a wonderful resource.”

Resources. Simply, Foote says, “Get equipment. Invest in probeware, graphical analyzers, and sensors. Let the world of technology into the school … support grant writing. Make STEM a priority.”

Relationships—within and outside schools. “STEM isn’t something that teachers sit down in a meeting and decide to do,” Foote says. “We have constant and ongoing communication about what we’re struggling to teach, what we’re doing and how we can support each other.” Projects like building a solar oven, for example, involve applied technology, math, and science teachers. Collaboration with the wider community leads to further opportunities. Teachers at Higley can discuss internship and educational requirements with local businesses through a chamber of commerce program called “Tours for Teachers.” “Not only do teachers visit the businesses, they visit us,” Foote says. “This provides us with an amazing classroom resource.”

TOOLS THEY USE

SOSSAMAN, HIGLEY UNIFIED

► Apps including Notability, Edmodo, IXL, and Ten Marks

► Arduino

► Autodesk Circuits

► Chromebooks

► Document cameras (HoverCam, HUE HD Pro)

► ElectroCity

► Interactive whiteboards

► iPads

► Notepad ++

► PASCO wireless probeware

► TI calculators

A CONCERNING DIAGNOSIS

When the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources declared Green Lake to be “impaired” in 2014 because it fails to meet optimal water quality standards, the diagnosis launched a groundswell of community action. Wisconsin’s deepest inland lake, at 236 feet, creates a unique environment for different species of fish as well as opportunities for tourism and recreation, explains Dan Starr, science teacher at Green Lake High School. The whole community, including local and state organizations, banded together to organize a movement to protect their treasured natural resource. And a Vernier/NSTA Technology Award provided equipment that helped make student involvement in these efforts a reality.

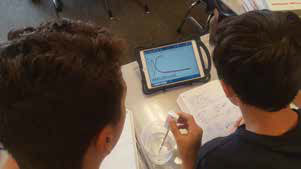

Phosphorus loads from various urban and agricultural sources are a possible cause of the low dissolved oxygen levels in the lake’s thermocline, but assessments of all aspects of the health of the lake and its tributaries are ongoing. Starr’s students, along with chemistry students in Jason Ladwig’s class, dove in with their Vernier equipment to measure temperature, flow, and turbidity as well as dissolved oxygen, pH, nitrates, and phosphorus levels. Engagement is high, Starr says, “especially when it’s working and there’s a boat involved.” Complications are part of real-world science, though, and “students need to be part of the process and appreciate that things aren’t always perfect,” he says.

While state-of-the-art data-collection technology gives students unprecedented opportunities, Starr points out that it’s also instructive, and fun, for students to measure such things as a waterway’s Biotic Index using low-tech equipment like nets, ice cube trays, and charts for identifying microorganisms.

Starr’s initial goal is for students to mirror the measurements “real” scientists are taking and eventually for students to join in the community discussions, present their findings, and even be involved in decision-making to help protect their lake.

A COLLABORATIVE ECOSYSTEM

None of this student work would be possible, Starr emphasizes, without collaborators in the wider community. As a result of these networks, students will work this fall with Mary Jane Bumby, a long-term water quality citizen scientist—seeing her equipment, comparing data, and learning about standards and best collection practices. The large boat needed for student data collection is provided by Mike Norton, a local charter fishing guide, who takes students out and shares tales of his work and the history of the lake. The DNR also provides its expertise and equipment through Water Action Volunteers (WAV), a statewide, citizen-based monitoring group. The Green Lake Sanitary District and the Green Lake Association have both provided invaluable support throughout the process to engage students with hands-on activities.

In another example of this kind of collaborative work that marries learning and real-world conservation management, a chemistry class, led by a teacher trained in collecting and packaging samples, collects monthly water samples and sends them to a state facility for analysis. The students benefit from the educational opportunity and from helping to make a difference, the state benefits from their volunteer efforts—and the Green Lake Sanitary District picks up the costs.

Starr is grateful for all of these relationships—with these organizations and with Vernier. “The students’ eyes brighten when they use this equipment and see it happen,” he says.

TOOLS THEY USE

GREEN LAKE HIGH SCHOOL

► Secchi Disks

► Vernier Colorimeter

► Vernier Deep Water Temperature Probes

► Vernier Dissolved Oxygen Probes

► Vernier Nitrate Ion-Selective Electrode

► Vernier pH Sensors

► Vernier Turbidity Sensors

EDUCATION IN THE REAL WORLD

The Kent (MI) Intermediate School District (ISD), a regional educational service agency in Grand Rapids, supports over 120,000 students in 20 public districts and also charter schools in all curricular areas, including STEM. They host a high-tech incubator school and an online high school and offer high-school courses at their campus including manufacturing, IT, and design; mechatronics; 3D animation; machining; and health careers.

Kindy Segovia, assistive technology supervisor, explains: “Our focus is to bring real-life experience and interaction with industry to the classroom for students of all abilities,” including professional development and research opportunities and partnerships with businesses and colleges and universities.

COMMUNITY AND CAREER CONNECTIONS

Career Readiness is one of the highly collaborative departments within Kent ISD, supporting staff and students to bring the real world to the classroom—and vice versa. Their community partners include the airport, a downtown retail and culinary venture, Habitat for Humanity, local health-care facilities, and a workforce development association. While not all districts have access to the kind of resources that Kent ISD provides, educators everywhere can follow their example of networking and connecting with local businesses.

The department has initiated several successful ventures that bring students into the workplace. Their job—shadowing program links students with professionals for after-school jobs, summer internships, and an annual day of learning and observation (on Groundhog Shadow Day). These experiences help students narrow their vocational focus and also broaden their options. Ebiri Nkugba, STEM consultant for Kent ISD, is proud to have been part of building a program with Kenowa Hills Public Schools in which students prepare for the workforce by attending classes in an actual workplace.

Students often find careers they love through these opportunities. One student wrote to thank Kent ISD. “Not only did the program help cement my career goals,” she wrote, “but it also helped me get my foot in the door for a job.”

EQUAL LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES FOR ALL

Yet another area of collaboration linked to STEM education in which Kent ISD supports students is in the area of assistive technology. Segovia feels fortunate to work in a place with such a broad reach and interdepartmental cooperation. When Nkugba sets up a new STEM initiative with a teacher, for example, he will consult with Segovia concerning tools and adaptive approaches to support the specialized needs of students with disabilities. Segovia often equips teachers with tools such as Tiggly and Osmo to help these students engage, learn, and create. Kent ISD’s large lending library of tech tools is another program that facilitates and enriches learning for staff and students. With these rich resources and collaborative enterprises, Kent ISD is preparing all students for future educational and vocational success.

TOOLS THEY USE

KENT ISD

► 3D printers

► Arduino

► littleBits

► NAO robot

► Osmo

► Raspberry Pi

► Tiggly

► UAVs (drones)

► VEX Robotics

FOR THE JOY OF MAKING

Michelle Carlson first learned of the Maker Movement when she was working at the Tehama County (CA) Department of Education. From her experiences with teachers and students, she “knew this could provide an amazing solution for engaging all learners and bringing more real-world connection and relevance back to the classroom.” She turned an underutilized space at the DOE office into a makerspace and watched her “vision to make learning joyful” come to life.

When district superintendents began approaching her about this work, she founded Future Development Group, LLC. And since May 2015 she’s collaborated with schools and districts including Vista Preparatory Academy, Evergreen Union School District, Maywood Middle School, in the Issaquah (WA) School District, and the Butte County Office of Education, as well as the local juvenile justice center.

Carlson focuses on “building capacity within systems, creating the spaces which allow for a ‘maker experience’ as well as mentoring teachers and school leaders with the goal of helping them to reach a point where they no longer need outside help.” It’s important, she notes, to have “a complete system of support” in place.

Knowing that most schools can’t afford a consultant to help them get started, Carlson put all of the curriculum, resources, and teaching from a successful program she created last year at Corning Elementary District into a book called 180 Days of Making: How to Incorporate Experiential Learning in Ways that Will Change the World for Your Students.

TRANSFORMATIVE COLLABORATION

Some of Carlson’s favorite collaborative moments include:

■ Seeing probation staff and incarcerated youth forging new relationships through making. Carlson says, “The kids have spoken about how the makerspace has helped them in dealing with strong emotions and in building up their confidence … which will help them in their re-entry into the outside education system.”

■ Helping to write grants so the Tehama County Arts Council could offer a successful “Maker Summer” program with free arts and maker workshops for families.

■ Partnering with San Francisco’s Exploratorium and Redding’s Turtle Bay Exploration Park to offer Maker Educator Meetups (MEM) at Turtle Bay.

■ Arranging a visit from Tinkercad specialists, who will talk about careers in design and fabrication and hold a 3D design session for teachers.

■ Watching local professionals she and friend Melissa Mendonca have enlisted as volunteers share their expertise (in graphic design, music, etc.) with students.

TEACHING A VALEDICTORIAN TO LOVE LEARNING AGAIN

A young woman called Maryn, who was her school’s valedictorian and is now in college, shared her transformative experience with making with Carlson: “In makerspace I learned the importance of failing … and getting back up and trying again and again. … With no expectations of success, I feel free to experiment and truly learn. … Makerspace … teaches you the stuff you don’t learn in the classroom, by applying all of the classroom stuff. And for most of us it taught us how to love learning again.”

TOOLS THEY USE

FUTURE DEVELOPMENT GROUP

► Adobe Creative Cloud

► Arduino kits

► KEVA Planks

► LilyPad Design Kit

► Makey Makey

► Parallax Robotics

► SparkFun Digital Sandbox

► Tinkercad

TRY THIS: THE PAPER BRIDGE PROJECT

Amidon-Bowen’s Jamie Ewing, who did this project during a NASA training, launches the activity by showing a PowerPoint of bridges—from rope bridges to highly engineered bridges.

CHALLENGE: To build the longest bridge between two chairs.

MATERIALS:

• 5 pieces of 8.5 x 11 paper

• 2 pieces of masking tape, each 3 feet long (1 roll for younger kids)

• 1 pair of scissors

Students should work in teams of no more than two or three. Once the challenge has started, answer no questions.

THINGS TO LISTEN FOR: Conversations on how to construct, what the definition of a bridge is, design, redesign, and evaluation of their work.

HINT: Ewing and his PreK students built one together as a class before the students did the challenge themselves.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.